John Adams brings urban darkness to vivid life with the New World Symphony

John Adams conducted the New World Symphony Saturday night in a program that included the local premiere of his "City Noir."

The celebrated composer John Adams came to Miami Beach Saturday and did it all: He led the New World Symphony in high-energy performance of Bartók’s Dance Suite. He served as the gracious on-stage host for the American composer Julia Wolfe. And he led the orchestra in the Florida premiere of his own atmospheric City Noir, a tribute to Los Angeles as seen through period crime dramas.

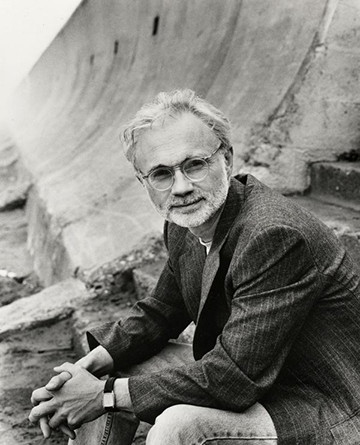

Adams, dressed in black that set off his white hair and beard, entered the hall at New World Center to loud, long applause. He picked up a microphone and described how all three works to be heard that night drew for inspiration on popular culture — whether it was rock music for Wolfe, Hungarian folk songs for Bartók or the steamy atmosphere of Los Angeles film noir for Adams himself.

The first work of the evening was Wolfe’s Arsenal of Democracy for brass, winds, piano and electric guitar. A co-founder of the New York new music collective Bang on a Can, Wolfe said the title referred to President Roosevelt’s description of the United States before the country entered World War II, a description that had turned ironic and absurd in her eyes under President Reagan.

Like many works of rock music, it aimed more for the gut than for the head. Hammering dissonant chords in set rhythmic patterns – broken by gasps of melody — set your insides vibrating. It didn’t vary much over the course of 13 minutes, being dominated by minimalist patterns of sound, but then not many pieces on first hearing leave with you with motifs still ringing in your ears a day later.

Adams’s City Noir was composed for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which premiered the work in 2009. As he explained from the stage, Adams here attempts to evoke Los Angeles as seen through the dark crime films that were set in the city.

“It’s an urban landscape,” he said. “It has some inspiration from the noir films of the 1940s and early 50s, and one from the 70s which I love, Chinatown, where Jack Nicholson spent 70 percent of the film with a bandage on his nose.”

It would have been easy for a composer of Adams’ vast gifts to write a crowd-pleasing period piece. But this work represents much more than that, using a blend of 1940s jazz, the smooth lyricism of Hollywood film scores and Adams’ highly personal, contemporary style to evoke images of rainy nights, Packard sedans, men in fedoras and run-down detective’s offices.

Adams wrote long soaring melodies for the violins, passages that went on and one without much repetition, creating a deeply atmospheric tone of danger, drama and romance. Violins rose to the challenge of these long, high melodies, with near-perfect intonation and phrasing that brought out the tension and menace of these passages.

Handling the extensive saxophone solos was guest musician Timothy McAllister, who performed the work’s world premiere and who was brought in at Adams’ request. Although seated in the middle of the orchestra, he stood for the solos and played the jazz-inspired riffs in a nervy, improvisatory style, a highlight of what was overall a fine performance. Carrie Schafer, one of the New World’s trumpet players, brought an ominous, sad, worldly-wise tone to solos that evoked the trumpet theme of Chinatown.

Bartók’s 1923 Dance Suite draws on the folk music of his native Hungary. Like a cafe violinist playing Gypsy music, the work presents a polished and smoothed-out version of the rough originals. Adams drew a vigorous performance from the orchestra. This was not one of those performances in which the energy consists largely of playing loudly and aggressively. The energy came from Adams’ and the orchestra’s ability to create great tension through the use of calibrated dynamics and tempos. The first section’s dance music in the violins, and in the fourth section a long wind melody over a nervous accompaniment in the strings came off particularly well.

Adams’ stage manner is informal and generous. He gave Wolfe the floor and asked her questions that drew her out about the work. After the performance of his City Noir, he singled out performer after performer and then individual sections of the orchestra for applause.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Sun Apr 3, 2011

at 1:12 pm

No Comments