Violinist Daniel Hope to pay tribute to his great predecessor Joachim

Daniel Hope will present a program inspired by the great 19th-century violinist Joseph Joachim Tuesday night at the Broward Center.

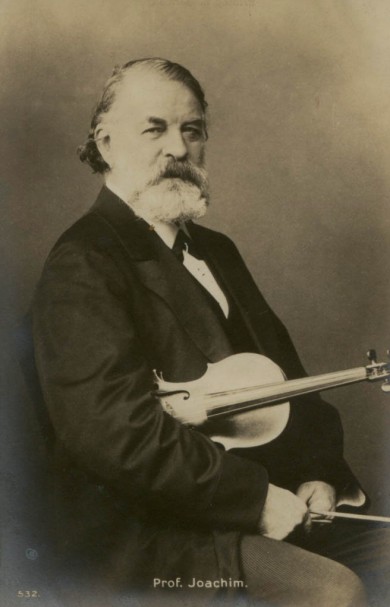

A violinist who builds a program around the legacy of the 19th-century virtuoso Joseph Joachim can hardly be accused of pandering to sell tickets. Consider the headline on a 2007 article in The New York Times commemorating the 100th anniversary of Joachim’s death: “Another Ovation for Joachim (Who?).”

Yet aside from the Italian virtuoso Niccolò Paganini, it’s difficult to think of a violinist who has exerted more influence than Joachim on the history of the instrument or on music in general.

As the confidante of some of the greatest names in 19th-century music, Joachim inspired, collaborated on and made famous some of the most significant works of the violin repertoire. The British violinist Daniel Hope will give a recital Tuesday at the Broward Center in Fort Lauderdale devoted to exploring the music we owe to this man whose name is still unfamiliar to the average concertgoer.

“His legacy has been massive,” Hope said. “There are so many works that are either dedicated to him or that he helped bring to the surface, one could spend literally years dedicating one’s energy to his legacy.”

Joachim, who lived from 1831 to 1907, was at the center of that passionate, intellectual, literary circle of Romantic composers and musicians that revolved around Robert and Clara Schumann. He was an intimate of Brahms, providing technical assistance on his Violin Concerto, composing the cadenza that still remains standard and giving the work’s premiere at Leipzig in 1879 under Brahms’ baton.

A feud with Brahms over Joachim’s estrangement from his wife produced another great work: the Brahms Double Concerto for Violin and Cello, composed as a makeup gesture toward the violinist. Joachim worked closely with the composer Max Bruch on revisions to his Violin Concerto No. 1, which remains one of the most popular works in the repertoire.

At a time when violin virtuosos such as Wieniawski, Vieuxtemps, Ernst and Sarasate were conquering audiences with Olympic-gymnast-style displays of technical prowess in their own showpieces and concertos, Joachim sought out the best works of the present and past. His advocacy moved the Beethoven Violin Concerto and Bach unaccompanied sonatas from the fringes of the repertoire to the central place they occupy today. He made the performance of chamber music a respectable occupation for a leading virtuoso.

“We owe the greatest concertos of history to him,” Hope said. “We owe the Beethoven concerto to him because, you know, it was a failure when it was first premiered in 1806. Nobody really wanted to take it seriously, until 12-year-old Joachim, with the encouragement of Mendelssohn, performed it in London and it brought the house down. From that moment on, the Beethoven concerto was restored to its rightful place as probably the greatest violin concerto of all time. So we even have that to thank him for.”

We can also thank him for Jascha Heifetz, the Suzuki method for teaching music, and Arthur Rubinstein. Joachim taught Leopold Auer, who in turn taught some of the greatest 20th-century violinists, including Heifetz, Mischa Elman and Nathan Milstein. Joachim taught the German violinist Karl Klingler, who in turn taught the young Japanese violinist Shin’ichi Suzuki who would go on to create a revolutionary teaching method that introduced thousands of children to music.

When Joachim headed the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, a young woman named Felicia Rubinstein traveled from Lodz in Russian-ruled Poland to consult the great violinist on the bizarre talent for the piano displayed by her three-and-half-year-old son Arthur. In his book My Young Years, Arthur Rubinstein describes how the gray-bearded, deep-voiced violinist set him at ease with his kindness as he tested his talent, humming the second theme of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and asking Arthur to harmonize it and transpose it to different keys.

A few years later, after Arthur had begun serious piano study, his mother took him to Joachim again. “Play a little Mozart for me, mein Junge,” Joachim said. And upon a satisfactory performance of the A Minor Rondo, he gave Arthur a bar of Lindt’s bitter chocolate and took his mother aside to discuss the boy’s future. Joachim agreed to supervise his education, arranged for Arthur to study with a leading Berlin teacher and raised the funds to pay for it all. And he insisted that the boy not be exploited as a child prodigy but first receive a good general education before going on the concert stage.

As an exemplary man of European culture, Joachim took a broad approach to life of the violin virtuoso that’s very similar to that pursued by Hope. Although the repertoire listed on Hope’s web page includes many of the standard concertos, his musical engagement encompasses raga, jazz and historically informed performances of the classics, including the premiere recordings of new editions of the Berg and Mendelssohn concertos.

Born in South Africa and raised in England, Hope attended the Royal Academy of Music and then served as violinist for the final six seasons of the celebrated Beaux Arts Trio. Today he lives in Vienna and cultivates a busy life of solo appearances, chamber performances and writing. He has authored three books in German, among them Familienstücke: Eine Spurensuche (Family Album: Following the Trail), a memoir of his family that traces the path of other families that fled chaos and hunger in Europe to South Africa, and Wann darf ich klatschen? – Ein Wegweiser für Konzertgänger (When do I applaud?” – A guide for concert-goers).

The Fort Lauderdale program, in which Hope will be accompanied by the pianist Sebastian Knauer, his longtime collaborator, includes the Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor of Edvard Grieg, a friend of Joachim who often performed with him. It includes the Scherzo by Brahms from the F-A-E Sonata, a work composed as a gift to Joachim by Robert Schumann, Brahms and Schumann’s student Albert Dietrich. Also on the program is Clara Schumann’s Romanze Op. 22 No. 1, which was dedicated to Joachim, the Brahms Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Major, Mendelssohn’s lieder Auf Flugeln des Gesanges and Hexenlied and Joachim’s own Romanze, Op. 2 No. 1.

In his book The Virtuosi, the late New York Times critic Harold Schonberg called Joachim “the greatest classical violinist of the 19th century” and the “stern, Jehovah-like corrective against rattle-brained exhibitionism.” But while Hope recognizes Joachim’s seriousness of purpose, he considers him as much a Romantic as his flashier contemporaries.

“For me romanticism is not about big juicy playing,” he said. “For me the Romantic era is about what really it meant in art and literature and painting. It was a very bold and very passionate approach to those genres, and yet done through introspection, and that was what Joachim was great at.

“He was not a virtuoso like Sarasate was, nor was he one like Liszt, but he was in the Romantic vein, very much of that time—-the idea that the artist was not just a performer but was in so many other ways attached to music through teaching, through poetry, through literature, through programming, through concert promoting. He incorporated, for me, a sense of what true Romanticism is.”

A final oddity of history distinguishes Joachim: He was the first great violinist to make recordings. In 1905, two years before his death, he recorded two movements of unaccompanied Bach, two Hungarian Dances of Brahms and his own Romance in C. Through the crackling surface noise of the recordings, you can hear the musical voice of one of the greatest instrumentalists in history, a survivor into the 20th century from the era of Schumann, Mendelssohn and Brahms.

“If you listen to some of his recordings on YouTube, admittedly it was at the end of his life,” Hope said, “But it’s a fascinating document to hear that sound, which is very pure, very sparing in vibrato and yet deeply felt at the same time.”

Violinist Daniel Hope and pianist Sebastian Knauer perform works associated with the violinist Joseph Joachim 8 p.m. March 18 at the Broward Center’s Amaturo Theater. browardcenter.org; 954-462-0222.

)

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Thu Mar 13, 2014

at 11:57 pm

No Comments