Baritone Kelvin Thomas, New World players deliver a fine musical madness

Kelvin Thomas performed Peter Maxwell Davies’ “Eight Songs for a Mad King” with New World Symphony members Sunday afternoon in Miami Beach.

In 1969 composer Peter Maxwell Davies shocked the British musical establishment with his Eight Songs for a Mad King. A music theater work depicting the deranged King George III, the score was the piece de resistance on the New World Symphony’s “Royal Portraits” program Sunday afternoon at New World Center in Miami Beach.

Scored for a six-piece chamber ensemble and actor-vocalist as the monarch, the work remains a stunning theatrical experience but fifty years have dimmed its shock value. In purely musical terms, Davies’ early collage score cannot compare to his significant later chamber and orchestral works or even his pops- concert standard Orkney Wedding with Sunrise.

The role of the king, originally conceived for South African actor Roy Hart, requires a performer with an extended vocal range and technique that goes well beyond the Sprechstimme (mixing singing and speech) in Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire.

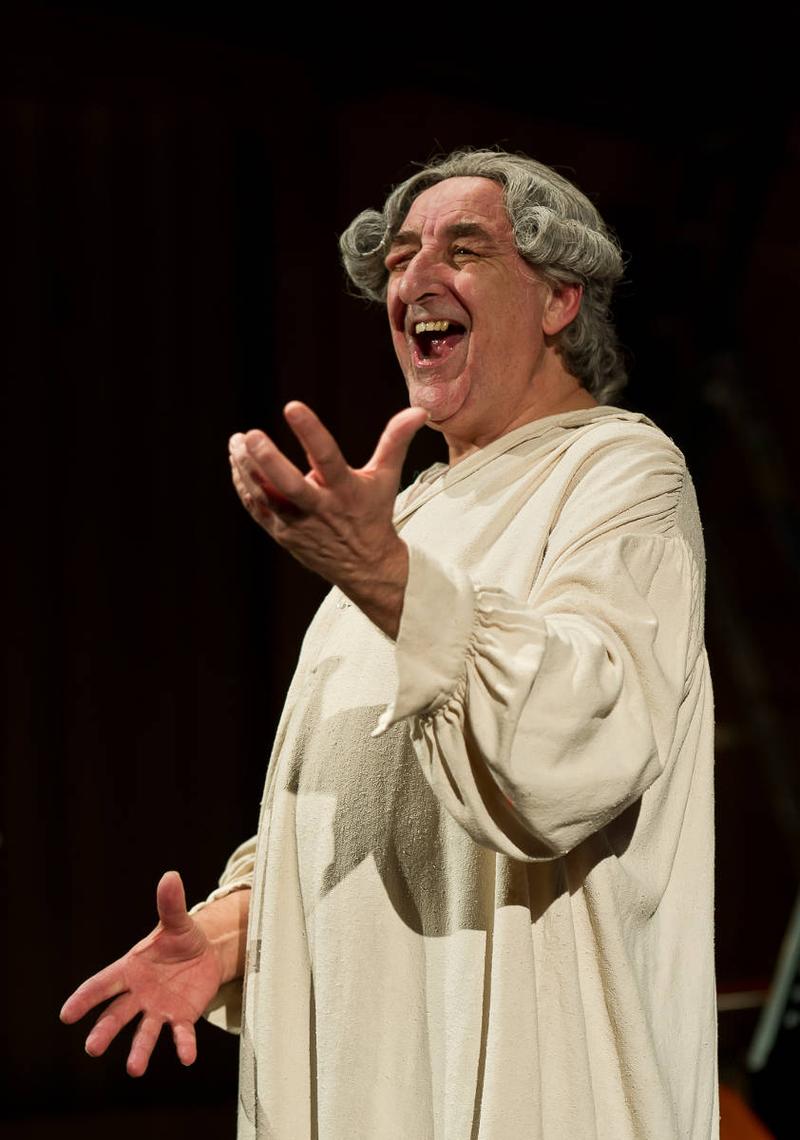

Kelvin Thomas has played this role numerous times and recorded it under Davies’ supervision. The British baritone was absolutely riveting. His impersonation of the once-triumphant leader was a devastating picture of egotistical hubris and insanity; his tortured speech, buoyant vocalism and rants in the voice’s highest reaches met every challenge the composer conceived and more.

As the deranged royal, Thomas pranced about the stage, at times singing in a pliant voice, at others screaming or going into the countertenor register. When he asked “Where is the Queen?” projections of a skeletal female and crown set an ominous mood. As he announced his own death, a skeleton right out of a horror film engulfed the backdrop (which previously showcased foliage and the palace halls). At the climax King George grabs and smashes a violin to pieces. What shocked audiences five decades ago now seems merely gratuitous and unnecessary in a compelling dramatic presentation.

The rear of the New World Center stage encompassed picture windows against which lighting and designs were projected. The flute and clarinet players were in two large cages at the front of the stage as the king’s birds and the violinist, cellist and keyboard players wore masks, an allusion to Pierrot.

As the monarch’s keeper, percussionist Charlie Rosmarin led the confused royal on stage at the outset and took him out raving and ranting through the audience at the conclusion before the production faded to darkness. Luke Kritzeck’s lighting and Kristina Rodriguez’s illustrations conjured up a flickering, eerie film noir aura that perfectly matched the work’s disturbing picture of mental illness. Victoria Olson’s costumes looked like a Disney fantasy gone off kilter. Staging by Thomas and Michael Linville was dramatically gripping and vividly conveyed the harrowing mental deterioration of the last king of America.

From the first crashing and screaming chords, the six players were totally on top of Davies’ demanding writing which is almost as difficult for the instrumentalists as the protagonist. Kayla Burggraf whirled through the high-lying flute solos and clarinetist Jesse McCandless vibrantly played the sudden fragments of ceremonial music amid the dissonance. Thomas Stiegerwald brought character and spice to the piano’s reminiscence of the king’s salon tunes. Margeaux Maloney was nothing short of dazzling in the fiendish violin writing (before the king silenced her instrument) and Alexa Ciciretti brought out the cello’s gruff tones as well as its resonance.

In addition to acting as the king’s guardian, Rosmarin was master of a wide array of percussive instruments, playing with emphatic agility. A better performance of this hybrid score could hardly be imagined. Whether it was worth reviving is another question.

The first half opened with two brief works by British Baroque master Henry Purcell. Violinists Scott Jackson and Michael Rau, violist Stephanie Block, cellist Blake-Anthony Johnson and Stiegerwald offered a lean, tautly paced reading of the Chacony in G minor. Blake-Johnson and Stiegerwald’s continuo lines came through with clarity. Joined by violist Spencer Ingersoll, the players gave a brisk and well-balanced performance of the Fantasia upon One Note with the violins and violas resounding in color and texture as one.

Beethoven’s Trio in B-flat Major for piano and strings (“Archduke”) is one of the masterpieces of the chamber music literature. Three talented New World fellows gave the work a capable performance that missed that extra spark which turns the music to incandescence.

Cellist Nicholas Mariscal was the trio’s class act. In recent weeks Mariscal has been a standout in a performance of Paul Hindemith’s bright and busy Octet and a stellar soloist in Khachaturian’s vulgar Concerto-Rhapsody. Mariscal brought depth of tone and technical mastery to every page. Moreover he alone seemed to probe the score’s heroic and lyrical subtext.

Pianist John Wilson, a fourth year New World member, has given many fine performances and he certainly had Beethoven’s keyboard writing well in hand but sensitivity of touch was wanting. Violinist Qianwen Shen, a substitute for the originally scheduled player, initially played merely efficiently but exhibited greater vigor and tonal sheen as the reading gathered momentum.

A vigorously articulated Scherzo and broadly phrased Andante cantabile ma però moto (the two middle movements) found the musicians at their best. The slow movement was indeed aristocratic with Wilson’s weighted piano lines never overpowering the strings. Minor-key episodes were given greater weight and darker sonority, displaying Beethoven’s remarkable transformative thematic invention. Although individual instrumental textures were clear and audible, the peasant dances of the concluding Allegro moderato needed greater lightness and verve.

The New World Symphony chamber music series continues 2 p.m. March 24 at New World Center with guest cellist Tamás Varga in performances of Korngold’s String Sextet, Haydn’s Flute Trio No. 17 and Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 2. nws.edu; 305-673-3331.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Mon Feb 11, 2019

at 2:09 pm

No Comments