Frost Symphony serves up a diverse lineup of American music with local connections

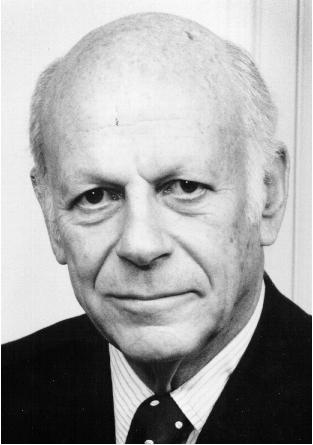

William Schuman's "New England Tryptych" was performed Wednesday night by the Frost Symphony Orchestra, a work that the same ensemble premiered in 1956.

The Frost Symphony Orchestra toasted the stylistic diversity of 20th- and 21st-century American music in an adventurous program led by Thomas Sleeper Wednesday night at the University of Miami’s Gusman Concert Hall in Coral Gables. Titled “An American Celebration,” the evening offered a repertoire perennial, works by two infrequently-heard American masters and an ambitious symphonic essay by a longtime Frost faculty member.

With tenures as president of the Juilliard School and founding president of Lincoln Center, William Schuman (1910-1992) was one of America’s most important educators and arts administrators. These significant contributions to the nation’s musical life have tended to eclipse his creative output. While associated with Aaron Copland and his circle of American symphonic composers, Schuman brought his own distinctive voice to a large output of orchestral, chamber, choral and dance scores. His bristling, sinewy soundscape and brilliant orchestration marked Schuman as an American original who did not adhere to any stylistic ideology or orthodoxy. His eight symphonies are some of the most important American works in that genre and deserve more frequent performance. Likewise his ambitious solo works for violin, cello and viola with orchestra deserve revival.

New England Triptych was once Schuman’s most frequently played work but, now, has largely fallen off the repertoire radar. It was apt programming for the work had its world premiere in 1956 by the very same ensemble, then the University of Miami Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andre Kostelanetz.

The three-movement suite is based on hymns and revolutionary anthems by 18th-century American composer William Billings. Far from a literal transcription, Billings’ melodies are filtered through Schuman’s mildly dissonant brand of 20th-century Americana. Sleeper’s exuberant leadership again energized his young musicians to a performance that transcended its student origins. A crack brass section gave the opening Be glad then, American that extra dash of fire. Silken string tones and eloquent solos by oboist Rachel Leuck and bassoonist Will Brubaker brought gravitas to Schuman’s surging reinvention of When Jesus wept. Piercing woodwinds propelled the contrapuntal intricacies of the stirring anthem Chester to a spectacular conclusion. Sleeper and the entire ensemble shone brilliantly in this worthy revival.

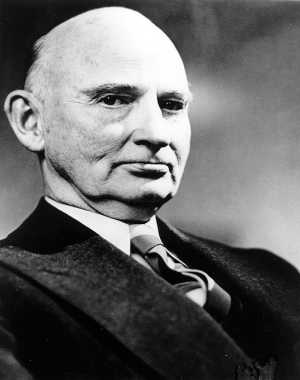

Carl Ruggles

Carl Ruggles (1876-1971)was one of American music’s great originals. A University of Miami composition faculty member from 1938 through 1943, Ruggles was a meticulous craftsman who constantly revised a small output of works, eventually retiring to his native New England to pursue a second career as an artist and painter. Angels (1921) was originally scored for trumpets alone. The composer’s 1940 revised version, presented by Sleeper, is a setting for three trombones and four trumpets. This solemnly atonal score is strangely moving and almost medieval in its spare austerity. Angels is the work of an iconic master who followed his own musical drummer, and the Frost brass players produced luminous sonorities, rich but never harsh.

Samuel Barber

Associate conductor Zoe Zeniodi led a deliberate but highly effective performance of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Stressing the familiar music’s elegiac aura, Zeniodi drew darkly reverberant tones from the responsive string section, allowing Barber’s melody to soar without heavy handed exaggeration.

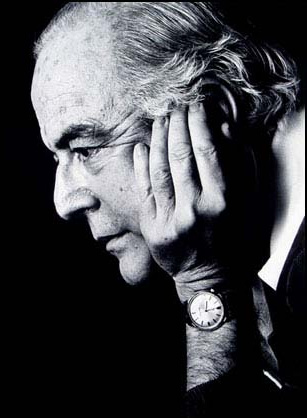

Frost faculty composer Dennis Kam’s Symphony No.1 was premiered at Festival Miami in 2001, shortly after the tragic events of 9/11. At that time, the piece seemed dense and overwrought. Kam revised the score in 2009 and that version received its first performance as the concluding work on the program. Tightened and considerably strengthened, Kam’s work now emerges as a well crafted symphonic essay, imaginatively scored for a large ensemble.

The lyrical ethos of Barber and stirring American pronouncements of Copland are felt in the symphony’s opening movement; yet nothing sounds derivative. In his pre-performance remarks, the composer said the second movement reflects feelings of warmth. Still, the recurrent five note figure seems to pose a question. When a strongly affirmative brass climax seems to provide an answer, the question motif returns again unresolved. The craggy principal theme of the finale suggests the rugged individualism of Ives and the resolute nationalism of Roy Harris.

Kam adopts cyclical elements by repeating thematic threads from the first movement. After brilliantly scored brass fanfares, the symphony comes to a sudden, abrupt, yet highly effective conclusion. Sleeper’s enthusiasm for this score was contagious and the Frost players outdid themselves with an intense, strongly accented reading.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Thu Mar 10, 2011

at 10:24 am

No Comments