Hindemith’s Octet gets a brilliant revival from New World chamber players

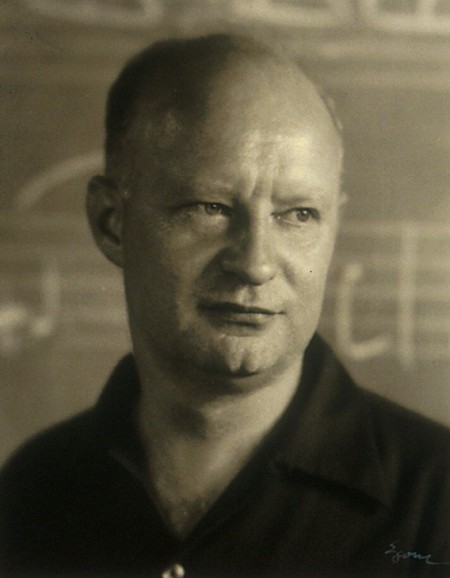

Paul Hindemith’s Beethoven-inspired Octet came back to life on Sunday at New World Center. Photo: Smithsonian/National Portrait Gallery

Hindemith’s works used to be orchestral and chamber mainstays but fell off the repertoire radar. Even his popular 1934 symphony, Mathis der Maler, famous also for displeasing Nazi censors, is rarely heard today. Hindemith wrote the Octet for members of the Berlin Philharmonic, and in acknowledgement of Beethoven’s celebrated Septet, but with a second viola added. (Hindemith was himself a distinguished violist and wrote several significant solo works for the instrument.) It was his final chamber score.

Arranged for clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, two violas, cello and bass, the Octet melds a neo-Baroque sensibility with an angular modernist twist. Demanding for the players individually and in ensemble, the work requires a performance of surpassing brilliance.

It received exactly that on Sunday. From the first bars, clarinetist Jesse McCandless stood out with a stellar combination of classical subtlety and freewheeling, jazz-virtuoso energy trained on the score’s often high-pitched writing. Andrea Beyer’s double bass solo in the first movement resounded with cello-like warmth and tonal depth. Dominic Brancazio commanded the agile leaps of the horn writing. Francisco Joubert Bernard exuded authority in the bassoon’s alternately rhythmic and melodic strokes.

Substituting on late notice for a New World fellow, violist Michael Klotz — of Florida International University’s resident Amernet String Quartet — brought out the thematic strands in Hindemith’s thorny counterpointing and nimbly executed the second movement’s rapid-fire solos.

The third movement brings out Hindemith’s lyrical side, and here the string players impressed. Nicholas Mariscal’s dark-tinged cello blended effectively with Klotz’s more acerbic sound, their voices enhanced by the tonal luster of Katherine Kobylarz’s violin and the mellow sonority of Daniel Fellows’ viola in a fine group effort.

To the last movement, ”Fugue and Three Old Fashioned Dances,” the eight players brought great clarity — each instrumental line delineated and transparent. A barely disguised waltz, polka and gallop concluded this superb rendition of the Octet with requisite charm and vigor.

The Octet was bookended by works of Haydn and Schuman that are in no danger of disappearing.

Haydn’s Quartet in D major was one of his final chamber scores and it remains an utter delight. In place of the more conventional sonata allegro form, Haydn ventured a first movement with a single theme and variations. Violinist Tara Lynn Ramsey showed idiomatic affinity for the music’s graceful aura by producing a sweet, mood-setting tone. The whole quartet then dug in at Haydn’s sudden accelerations, their blend becoming more gutsy and robust.

The Largo: Cantabile e mesto second movement finds Haydn at his most melodically inspired, and on Sunday the quartet responded with near perfect communion. Ramsey and Sergio Carleo on violins merged with the darker vibrations of Stephanie Block’s viola and Ian Greenberg’s cello in seamless major- and minor-key alternations.

Block was particularly outstanding with Haydn’s quirky and jokey twists in the final two movements, all expertly conveyed. Greenberg’s incisive solo in the central section of the Menuetto brimmed with vigor, and Ramsey fully encompassed Haydn’s imitation of country fiddling in the finale.

Schumann’s Quartet in E-flat major for piano and strings, one of the great works of the romantic era, concluded the heady program and took a full movement to catch fire. The opening Allegro brilliante, though precisely played, was too carefully pitched at a lowered emotional temperature, when more impetuosity and ardor was needed. Pianist Thomas Steigerwald’s low-key, finely sculpted approach seemed more appropriate to Mozart than Schumann.

The performance improved in the second movement. Jessica Pasternak’s deep hued viola brought gravitas to the slow march. Violinists Yefim Romanov and Dillon Welch, and cellist Michael Frigo, took flight in the contrasting thematic material, injecting a needed touch of poetry. The tripling figurations of the Scherzo were given both lilt and heft. An effectively high-speed version of the final Allegro ma non troppo was capped by the fugal return of the score’s opening theme, forcefully rendered.

The New World Symphony’s chamber music series continues 2 p.m. February 10 at New World Center with Purcell’s Chacony in G minor and “Fantasia upon One Note”; Beethoven’s Archduke Trio; and Peter Maxwell Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King, with baritone soloist Kelvin Thomas. nws.edu; 305-673-3331.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Mon Jan 21, 2019

at 1:50 pm

No Comments