Orchestra Miami to present a Kurt Weill rarity with “The Road of Promise”

Kurt Weill’s The Road of Promise will be performed by Orchestra Miami this weekend at Temple Emanu-El in Miami Beach.

“The idea is to bring people in and experience a place.”

That is Elaine Rinaldi, artistic director of Orchestra Miami, describing her concept for the ensemble during a recent phone conversation. The conductor says her goal for the orchestra’s performances, beyond playing, is for audiences to “Discover Miami Through Music,” as the name of the orchestra’s series goes. “We play in historic places, with programs tailored to landmarks,” so Miamians can learn more about their city.

The latest site for music and exploration is Temple Emanu-el, where this weekend Orchestra Miami, a 100-plus member chorus, and vocal soloists will perform Kurt Weill’s The Road of Promise, a shortened concert version in English (made by Ed Harsh) of his large-scale opera-oratorio The Eternal Road.

The original work, created by Weill and librettist Franz Werfel, is a four-hour narrative of the story of the Jewish people, with scenes from the Old Testament, including the saga of Moses in Egypt, the story of King David, and of the building of the Temple, set inside a framework that takes place in a modern setting. For Rinaldi, this is part of the appeal: “The piece takes place inside a synagogue,” she points out, with a Rabbi (tenor Allan Glassman) leading the drama into the historical stories. The cast also includes baritone Mark Delavan in the triple role of Abrahah/Moses/Jeremiah, and soprano Elizabeth Caballero as Rachel.

There are multiple layers of history in this project, beyond bringing people into Temple Emanue-el, an important historical and social landmark in Miami. It is regarded as one of the most beautiful synagogues in the country, and makes the claim to be the “oldest Conservative congregation on Miami Beach,” founded in the 1930s. That makes the congregation a historical companion to Weill’s original work, in more ways than one.

The work was commissioned by American writer and Zionist activist Meyer Weisgal as a way to warn America, and the world, of Hitler’s persecution of Jews in Germany. In the drama, Jews are hiding in a synagogue from a pogrom that is raging outside, and it is in this setting where their history is retold. The Eternal Road premiered in New York City in early 1937, received a rave review from The New York Times, and then was lost to history until a revival in Germany (and then Brooklyn) at the end of the last century.

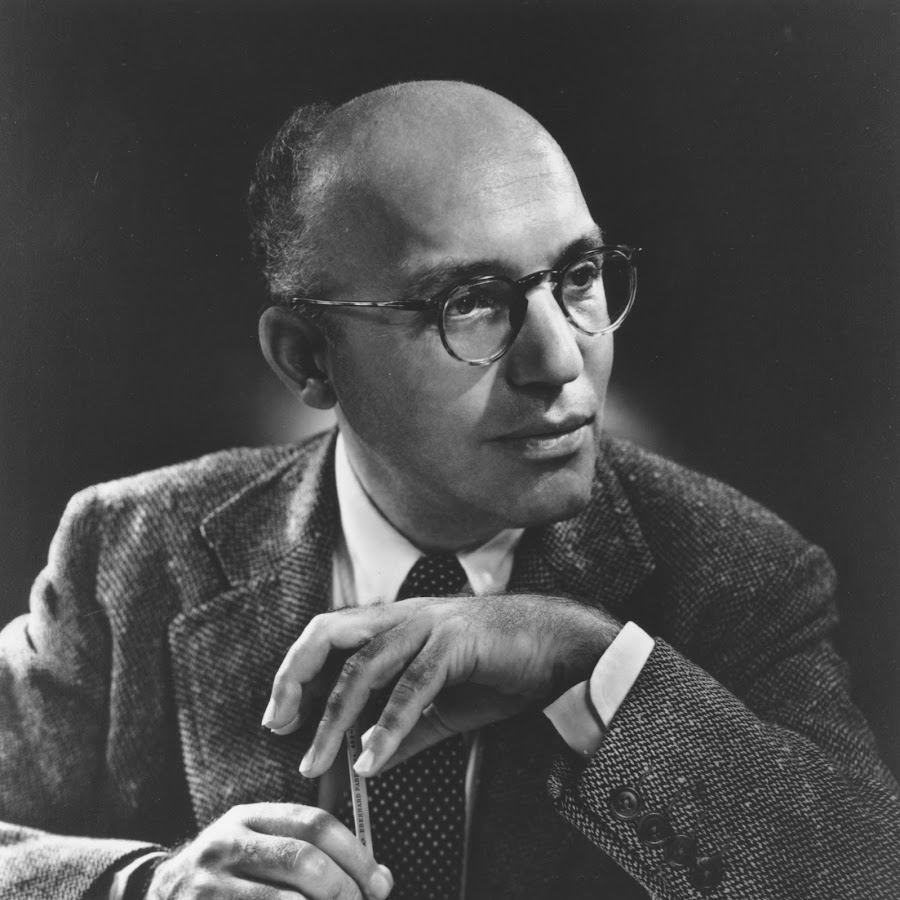

Weill’s four-hour musical pageant, The Eternal Road was premiered in New York in 1937. Photo: Lucas Pritchard.

The cycles of history that repeat themselves inside the piece are also returning outside, Rinaldi grimly points out, with anti-Semitism rising in America. While there will be no real sets, this performance will be semi-staged, with the singers in costume and a few props, and RInaldi shares that director Vernon Hartmann “wants the audience to feel part of the performance, seeking shelter from the pogrom.”

This is not just a Weill rarity, but on the overall music scene nationally a relatively, and surprisingly, rare Weill performance (there is a 2016 live recording) for a composer who is both well-known and obscure. There is the fame of his name, The Threepenny Opera, and “Mack the Knife,” but there’s little other general appreciation of his work.

Weill was prolific in more than one language, keeping an elegant, witty, and earthy core style while adapting his composing to the country, and venue, where it would be heard, from opera houses in Weimar Germany to France to America, and the Broadway of Street Scene, Lady in the Dark, and Lost in the Stars.

Rinaldi herself is experienced with Weill’s work, and last year produced “Airborne” with Orchestra Miami, a concert set in the old Coastguard aircraft hangar in Coconut Grove, where the program was Marc Blizstein’s Airborne Symphony and Weill’s Der Lindberghflug, an oratorio on Charles Lindbergh’s trans-Atlantic flight (with libretto by Bertolt Brecht), originally meant for radio broadcast. A niche work, certainly, but a stylish one specifically meant to be heard by a mass audience.

Above all, that is the audience Weill always spoke to, no matter the language or translation, and Rinaldi sees that strength in The Road of Promise. She points out that the Harsh adaptation has already done a lot of the work to make it companionable, cutting the length down to a little more than two hours. “He did the work for me,” Rinaldi says, emphasizing that the music in the adaptation is consistently strong. “The choral pieces are stand-outs,” she says, and they are some of the most luminous Weill wrote, while the composer’s bright angles and strong sense of a beat remain as clear as always. She adds that the “writing for Moses is breath-taking.”

The music also has that special Weill sound, a burnished glow of brass and woodwinds, lyrical and melodious vocal writing, and a central emotional stability that supports a feeling of determination and hope even through the most agitated music and the worst moments of this history to which The Road of Promise bears witness.

Rinaldi returns to this history again, and brings Weill directly into the picture. “You hear he was the son of a rabbi,” through the music, she says, pointing out that a section starts out with the Kol Nidre, and that much of the music is “has that Weimar flavor, and it’s often very cantorial.”

“He still has one foot in the old country … and also, there’s show tunes!”

Orchestra Miami performs The Road of Promise 8 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday at Temple Emanu-el. orchestramiami.org

George Grella is a regular contributor to New York Classical Review, Financial Times, The Wire, Bandcamp Daily, and other publications. He is the music editor of The Brooklyn Rail and the author of Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew (Bloomsbury).

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a Comment

Thu Feb 2, 2023

at 10:52 am

No Comments