Schwarz, Frost Symphony deliver rich advocacy in “Americana” program

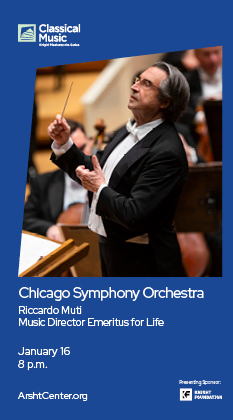

Gerard Schwarz conducted the Frost Symphony Orchestra in music of Diamond, Copland and Dvořák Saturday night at Gusman Concert Hall. Photo: Izzi Guzman

Has any currently active conductor led more American music than Gerard Schwarz? Throughout his career, Schwarz has been a tireless advocate for homegrown composers, leading innumerable premieres and programming significant scores from the nation’s creative heritage.

On Saturday night, Schwarz directed the Frost Symphony Orchestra in “Americana,” at the University of Miami’s Gusman Concert Hall featuring scores by two of the United States’ finest composers and a classic by a Czech master that forged a vision for the country’s musical sound.

David Diamond (1915-2005) was one of America’s most important symphonists. He wrote eleven symphonies and a large output of orchestral and chamber scores. Once semi-regularly played by major orchestras, his music has fallen out of fashion but Schwarz, who knew the composer, has continually conducted his works.

Diamond’s Symphony No. 4 was written in 1945. A compact three-movement opus lasting about 16 minutes, the symphony speaks with a clearcut nationalistic voice, bereft of quotations from folk or patriotic songs. The opening Allegretto surges with lush thematic motifs and urgent rhythms. The central Adagio envelops lustrous string and wind textures while clarion brass introduce the bustling Allegro finale. Throughout the symphony, Diamond’s forceful creative personality makes a traditional form sound new and fresh again.

Schwarz continually draws the best from the student players. He shaped the central movement eloquently, illuminating inner detail from the orchestral fabric and elicited high precision from the entire ensemble in the rapid outer movements.

The orchestral suite from the ballet Appalachian Spring is one of Aaron Copland’s most frequently played works and for good reason. Choreographer Martha Graham’s 1944 ballet is set in 19th century Pennsylvania Shaker farm country and Copland’s music reflects bucolic barn dances, a young couples’ love and communal gatherings. The 1945 suite is an enlargement for full orchestra of the original scoring for chamber ensemble which was dictated by the size of the pit in the theater where the dance was first performed.

Copland’s melodic inspiration and orchestral mastery are at their peak in this American standard, which continues to astound the listener, especially when conducted with the stylistic affinity, fluidity and sense of atmosphere that Schwarz brings to it. His invigorating reading ideally blended crisp rhythms and lyrical grace. Brass climaxes emerged firm and string attacks were razor sharp.

The variations on the Shaker song “Simple Gifts” were surely paced and the final orchestral statement properly stirring. Schwarz brought warmth and elasticity of phrasing to the quiet coda which was beautiful and organic (rather than the anticlimax it can sometimes seem like after the Shaker Variations). The orchestra’s playing was consistently excellent with especially fine solo contributions from concertmaster Jiaquiu Yu, flutist Abby Peel and clarinetist Santiago Oviedo Reina.

When Antonin Dvořák came to America in 1892 to become director of the National Conservatory in New York, he outlined a creative path for classical composition by American composers. He believed the music of African-American spirituals and native American songs and dances could be the basis for a new American concert repertoire, (In many ways, Copland and George Gershwin fulfilled that prophecy, albeit in a stylistic manner that Dvořák would not have recognized.)

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor (“From the New World”) was his last work in that genre, and represented his own contribution to the cause. Conceived in 1893, the symphony is indeed a product of the composer’s American odyssey, its thematic elements different from the distinctively Czech melodies that populate his previous eight symphonies.

In typical fashion, Schwarz reinvigorated a familiar orchestral warhorse. After a leisurely but concentrated introductory Adagio, Schwarz took the Allegro molto at a fast, sprightly clip. As the first movement progressed, the performance gathered power, energy and momentum. Crucial wind lines that are often obscured were clear and transparent.

The famous Largo was spaciously shaped and while the English horn solo was clearly rendered, it wanted a more rounded, projected sonority. Incisive string articulation in the central segment and the unanimity and solidity of the lower brass in the introduction and conclusion stood out.

The dance-infused phrases of the Scherzo sped forward like a force of nature and the trio sparkled, the winds artfully blended and balanced. There was fierce drive in the initial statement of the Allegro con fuoco finale and nice contrast in the clear and burnished clarinet subject, ably played by Jesse Winslow. Schwarz elicited huge climaxes from the full contingent while giving strong emphasis to the final quiet and sustained wind chord.

The entire performance spotlighted the conductor and orchestra in top form. Repeatedly recalled to the stage, Schwarz generously asked numerous individual players to stand and share the enthusiastic response.

Gerard Schwarz conducts the Frost Symphony Orchestra in de Falla’s Suite from The Three Cornered Hat, the world premiere of a centennial commission by Etienne Charles, Mahler’s Totenfeier and a Mozart piano concerto TBA 7:30 p.m. February 8 at UM Gusman Concert Hall in Coral Gables. frost.miami.edu

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Sun Nov 17, 2024

at 7:35 am

No Comments