Cellist’s offbeat tastes are hitting the mark

Mark Kosower

When Mark Kosower takes the stage, or sanctuary, Thursday night at Coral Gables Congregational Church, his recital will offer fare by familiar names like Bach, Mendelssohn, and Poulenc.

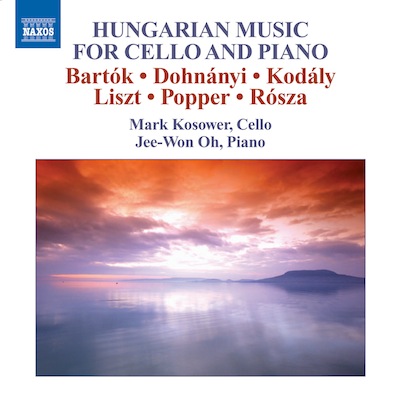

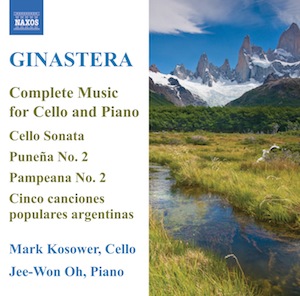

But it is his taste for the repertorial path less traveled that is garnering increasing renown for the 31-year-old cellist from Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Kosower and pianist Jee-Won Oh will also perform rarely heard music by Alberto Ginastera, Zoltan Kodaly and David Popper, composers represented on their two recent Naxos recordings: the complete cello works of Ginastera and a bracing disc of Hungarian music for cello and piano.

“What’s important when you play any music is to understand the musical stresses that go along with the language that is the mother tongue of the composer,” says Kosower. “With Hungarian music you have to have the strong yet flexible downbeat that trademarks all Hungarian music. You also have very long lines and high arching phrases, yet at the same time a very flexible tempi that accompanies this music.”

Kosower’s well-filled disc includes a wealth of stylistically varied material. Erno Dohnanyi’s Cello Sonata in B flat minor is the most substantial work, but there’s also Miklos Rozsa’s late solo showpiece, Toccata capricciosa, written for Piatigorsky; Popper’s Mazurka and Serenade; and transcriptions of Bartok’s First Violin Rhapsody and Liszt’s song Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth.

Kosower’s well-filled disc includes a wealth of stylistically varied material. Erno Dohnanyi’s Cello Sonata in B flat minor is the most substantial work, but there’s also Miklos Rozsa’s late solo showpiece, Toccata capricciosa, written for Piatigorsky; Popper’s Mazurka and Serenade; and transcriptions of Bartok’s First Violin Rhapsody and Liszt’s song Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth.The disc also includes Zoltan Kodaly’s lovely Adagio, a Kosower favorite, originally written for violin. “This is one of Kodaly’s early works that has a distinctly Hungarian flavor,” says the cellist. “But at the same time it also shows the strong influence of Brahms, which you wouldn’t necessarily expect.”

The brilliantly colored Variaciones concertantes makes an occasional concert appearance when an orchestra feels the need to add Latin color to standard classical programs. But 25 years after his death, much of Ginastera’s music remain in the shadows, his chamber and instrumental works in particular. “Ginastera is an underrepresented composer,” says Kosower. “He’s an interesting case: he’s famous and everyone knows his name, yet a lot of his music isn’t performed very often.”

Though the musical styles are as different as their national homelands, there are similarities between the Argentine Ginastera and the Hungarian Bartok. Both composers delved deeply into their nation’s folk music, transmuting its naïve essence into a modern esthetic while adding an astringent modernist edge.

Though the musical styles are as different as their national homelands, there are similarities between the Argentine Ginastera and the Hungarian Bartok. Both composers delved deeply into their nation’s folk music, transmuting its naïve essence into a modern esthetic while adding an astringent modernist edge.The Pampeana No. 2, which he will perform in Coral Gables, is one of three in that series, along with No. 1 for violin and No. 3 for orchestra. As indicated by the title, all were inspired by the Pampas, the rolling green plains south and west of Buenos Aires, where Ginastera loved to take long walks.

“There’s a haunting solitude at times and also in the faster sections he conjures up images of the gauchos galloping on horseback through the Pampas,” says Kosower. “It’s striking and there’s a lot of fire—it’s kind of Argentine cowboy music.” By contrast Ginastera’s Cello Sonata (1979) shows the composer moving in a more experimental direction. “Tonally, the late works become more advanced,” says Kosower. “He started incorporating a lot of avant-garde techniques and cluster writing within the harmony. But at the same time the music is very straightforward because the rhythmic drive and excitement propel it, so it’s always appealing to an audience.”

Married for seven years, Kosower finds it amusing how often cello-playing colleagues wind up marrying pianists, like himself and Oh, the Emerson String Quartet’s David Finckel and Wu Han, and others. “Of course, cellists always need a pianist,” says Kosower with a laugh. Also, perhaps, says Kosower, it could just be that the personalities of cellists and pianists are more complementary than that of other instrumentalists. “There’s always the joke that cellists are silently competitive, violinists are outwardly competitive, and pianists just don’t talk to each other at all!”

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a Comment

Mon Jul 28, 2008

at 8:55 pm

No Comments