“Porgy and Bess” scores a triumph in belated Chicago debut

CHICAGO —It took a long pull to get here — more than seven decades — but like its crippled, determined protagonist, George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess is finally on its way. The Lyric Opera of Chicago opened its rousing, magnificent revival of Gershwin’s masterwork Tuesday night in a triumphant local premiere. With the same production moving to San Francisco Opera in June, it appears that Porgy may finally be getting the belated attention it has so long deserved.

Gershwin’s operatic fable has always held a strange, ambiguous place in the nation’s musical fabric. Porgy is bursting with standards (lyrics by Ira Gershwin and DuBose Heyward, upon whose novel the opera is drawn), which, in large part, define the Great American Songbook. Yet even with all its fame and familiarity, Gershwin’s ground-breaking mix of popular song and legitimate opera remains a rarely performed work in opera houses — partly the logistics of fielding a huge, black cast and large chorus, but also, perhaps, the lingering, erroneous perception that Porgy is a work of musical theater and not a genuine opera.

At its 1935 premiere, Porgy and Bess was largely derided by most of the musical establishment: the composer and influential critic Virgil Thomson was dismissive, and even the usually perceptive Aaron Copland seemed baffled. Gershwin himself never doubted his achievement; as with Mahler, it took decades for the rest of the world to catch up, and, in Gershwin’s case, recognize the innovation, brilliance and rich humanity of this extraordinary work.

The indelibility of its songs has kept Porgy and Bess alive but it is the swagger and remarkable sophistication of Gershwin’s operatic skill that make it such a work of genius: the complex multipart writing for solo voices in the funeral and hurricane scenes, the orchestral fugue in the fight, the seamless mixing of grand opera with blues, jazz, gospel, and Southern Baptist fervor; even Gershwin’s sheer audacity, as when Crown rips into a scandalous blues ode in the middle of the others’ prayers at the height of the hurricane scene.

The Lyric Opera has imported the Francesca Zambello production first presented in Washington, which is largely successful and hews to a traditional view. The action is slightly updated to the 1940s, and Zambello’s few tweaks are improvements, such as a more theatrical and dramatically satisfying climactic fight between Porgy and Crown.

Zambello wisely divides the three-act opera into two large halves, the interval coming after Bess’s capitulation to Crown in Act 2. This staging is not quite complete, with several traditional trims (parts of the gambling scene and Porgy’s homecoming) as well as dispensing with Jasbo Brown’s bluesy piano opening and Porgy’s Buzzard Song. Maria gets her broadside against Sporting Life, however, I hates yo’ struttin’ style, sung with great relish by Marietta Simpson.

The only quibble I had with the staging was Peter J. Davison’s unit set for Catfish Row. While the towering five-level structure offers a striking visual, it suggests more an industrial rustbelt tenement, with little Southern atmosphere or suggestion of Charleston, much less Kittiwah Island in Act 2.

The story of the triangle between the crippled beggar Porgy and the drug-addled but repentant Bess — menaced by her former lover, the murderous Crown — is unsparing in depicting the cruelty, social ills and explosive violence of Catfish Row. Yet there is also great humor, kindness and humanity, and the love story between the solitary Porgy and the reformed Bess remains extraordinarily touching. When Bess has slipped back into the clutches of the oily Sporting Life and departed for New York, and the heartbroken Porgy hitches his wagon to find her, the opera’s finale is intensely moving in its affirmation and very American in its sense of hope against all odds.

The Lyric Opera has assembled a glorious cast of singers for these performances, virtually faultless from top to bottom. The serendipitous fact that Chicago’s first Porgy is opening exactly two weeks after the nation elected its first black president — from Chicago, no less — added a further layer of pride and historical weight to Tuesday’s opening performance.

Gordon Hawkins’ long experience was manifest as Porgy. The burly baritone conveyed the handicapped man’s great dignity, his superstition, even his self-loathing at his inability to confront Crown, as well as Porgy’s clear-eyed yet indestructible love for Bess. Vocally, Hawkins’ dark timbre at times seemed unevenly projected Tuesday night, with I got plenty o nuttin’ a bit undersung. But Hawkins rose to all the big moments, with a soaring rendition of Bess, you is my woman now, and, passionately put across Porgy’s emotional anguish at Bess’s desertion and his determination to find her.

As Bess, Morenike Fadayomi was simply sensational. The leggy English soprano was both sexy and dramatically convincing as the slatternly booze-swilling goodtime girl, Fadayomi charting Bess’s evolution from irresponsible addict to penitent, loving woman and back again with superb dramatic conviction. Vocally, her ample voice was assured in all the role’s myriad challenges, soaring in Oh, I can’t sit down, beautifully blending with Hawkins in the celebrated duet centerpiece, and vitally conveying Bess’ conflicted torment when falling again under the influence of Sporting Life’s “happy dust.”

As Crown, Lester Lynch was an imposing villain, as the alpha-male counterpoise to Porgy, displaying a big, ripe baritone and singing with malevolent intensity. It will be fascinating to experience this production when Lynch performs the role of Porgy in the second cast.

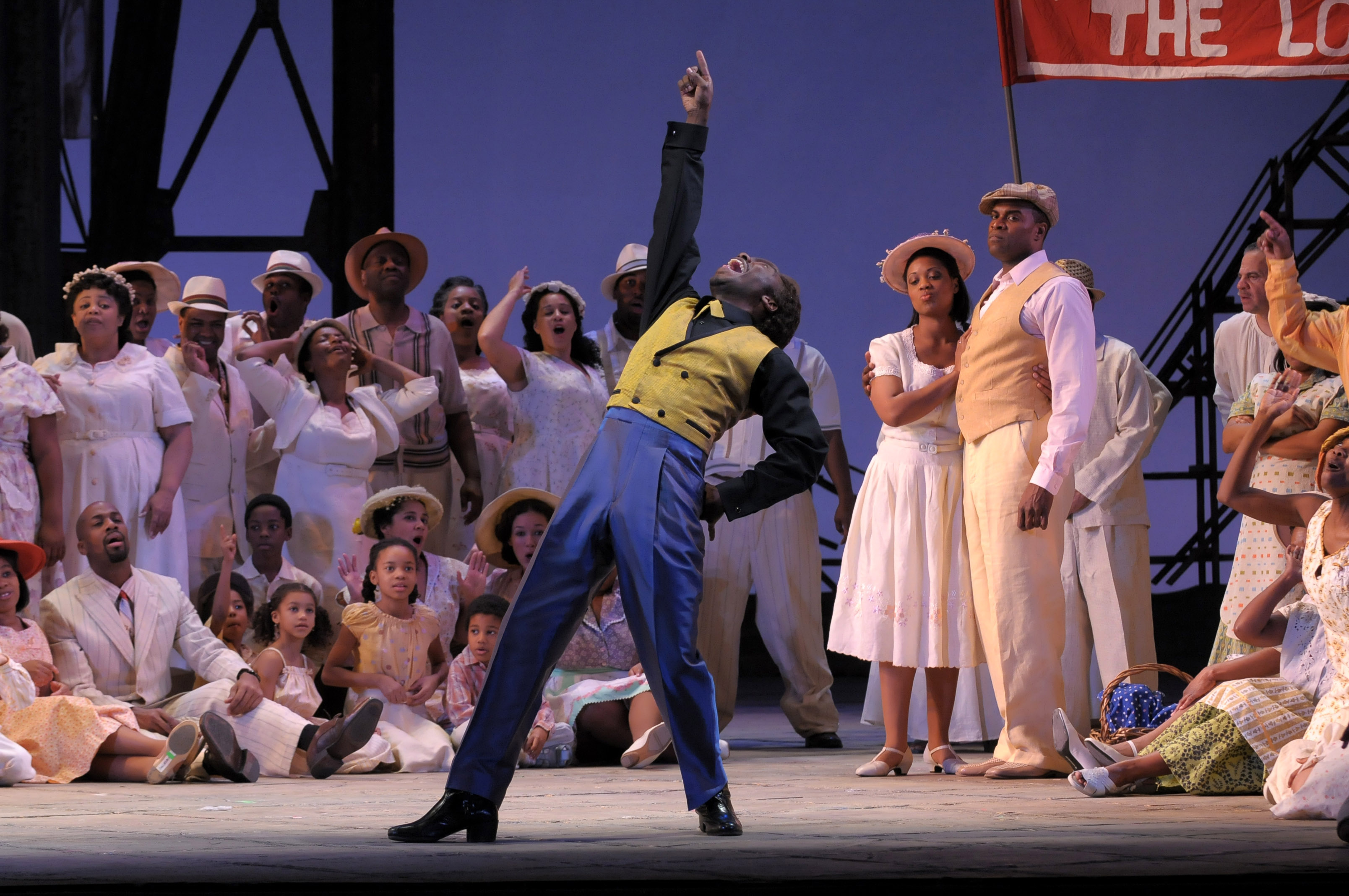

Gershwin was generous with his material, giving all of the large supporting cast their moments to shine. As the drug-dealing cynic, Sporting Life, Jermaine Smith managed to walk the tricky line between charm and villainy, vocally in the sinuous high tenor tradition with the requisite loose-limbed athleticism. His very free It ain’t necessarily so could have been more evenly sung, but Smith’s enticement of Bess in There’s a boat dat’s leavin soon for New York was a showstopper and the tenor brought theatrical panache and a dancer’s grace to the role.

Laquita Mitchell as a sweet Clara and Eric Greene as a hearty, big-voiced Jake were terrific as the ill-fated couple. Mitchell opened the evening with a richly sung, languorous Summertime, answered by Greene’s lovingly mocking A woman is a sometime thing. Jonita Lattimore has been a fixture on Chicago’s music scene for years, and the soprano was ideal casting as the religious Serena, delivering a febrile and intensely sung My man’s gone now.

Experiencing the entire opera on stage reminds one that the large chorus is, in effect, one of the major characters, and the wonderful ensemble of African-American singers was a lively characterful presence, providing rousing and vivid lift to Goin’ to the promised land and Oh Lawd, I’m on my way, surely directed by chorusmaster Donald Nally.

It was John DeMain whose Houston Grand Opera production in 1976 (and subsequent recording) helped to start Porgy and Bess on its road to revival, and so it is fitting that DeMain is leading these performances. The conductor’s experience and deep empathy for this score was apparent in every bar, drawing out the lyrical moments, never swamping his singers, and investing the big choral moments with bristling vitality.

Zambello’s direction can sometimes draw undue attention to itself, but here her staging was truly the art that conceals art, moving the action fluidly and providing inspired direction of the omnipresent chorus and many extras that brought Catfish Row to vivid theatrical life.

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess runs through Dec. 18 at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, with an extra performance just added on Dec. 16. $32-$197. 312-332-2244. www.lyricopera.org.

[Photos by Dan Rest for Lyric Opera of Chicago.]

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a Comment

Wed Nov 19, 2008

at 7:02 pm

No Comments