Lakme rises again to sing like a bell and die by a flower

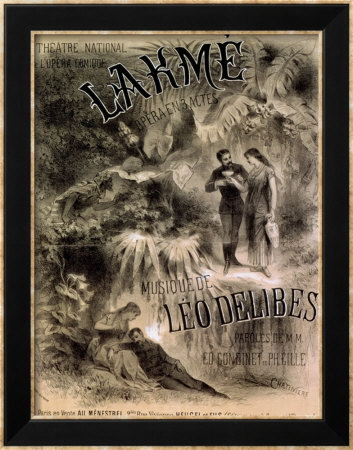

“Lakme, a neglected nosegay of 1883, is hardly a neglected masterpiece by modern standards,” sniffs the Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera, which goes on to state that Leo Delibes’ opera comique “has neither the melodic richness, nor the emotional intensity, nor the musical characterization found [even] in the Italian bel canto repertory.”

Other commentators throughout the 126 years since Lakme premiered in Paris have been hardly less generous. Yet Delibes’ ill-fated exotic romance is a stronger, more nuanced and rewarding work than many give it credit for, the Met Guide notwithstanding.

In addition to the celebrated Bell Song, there’s the lilting Act 1 Flower Duet, two soaring tenor arias, a gorgeous love duet, and some snappy ballet music, as one would expect from the man who created Sylvia and Coppelia.

“What’s amazing is how really beautiful the music is,” says soprano Leah Partridge. “It’s surprising to me that this music isn’t performed more often or excerpted in concert.”

Partridge will perform the title role of the tragic Indian princess in Florida Grand Opera’s production of Delibes’ Lakme, which opens Saturday night at the Adrienne Arsht Center.

Daughter of the Brahman priest Nilakantha, Lakme falls in love with Gerald, a British officer. The Anglophobe Nilakantha is furious at discovering the romance and he forces Lakme to sing the exotic Bell Song to entrap Gerald, who is stabbed.

Lakme hides him in a secluded forest retreat and nurses the wounded Gerald back to health, but soon his comrade-in-arms Frederic finds him. Gerald decides to return to his regiment and the heartbroken Lakme commits suicide by eating a poisonous flower thereby saving her lover’s life with her own sacrifice to the Brahmin gods.

The celebrated Act 2 Air des clochettes or Bell Song, has kept the opera’s name alive, with its extended Oriental vocalise, a showpiece beloved of coloratura sopranos and canary-bird fanciers throughout the early and mid-20th century.

Pierre Loti’s thinly disguised autobiographical tale is based on the author’s liaison with Rarahu, a native girl of Tahiti. Delibes and his librettist, Philippe Gille, were intrigued by the exotic locale and tragic love story but transferred the action to India to introduce a tense counterpoint of ethnic and religious hostility between the Brahmans and the English.

Another significant change was the manner of the heroine’s death. The actual Rarahu died not from a selfless suicide but indelicately—and less expeditiously—from acute alcoholism. Delibes had Gille change the story to a more poetic coda by having Lakme consume a poisonous flower. The fact that the plant Delibes selected, datura stramonium, wasn’t remotely lethal, was of little concern to the composer. “For me, the datura is poison,” he told Gille. “If it isn’t, there can be no opera.”

Even with the narrative’s stilted elements, Delibes’ musical treatment is more varied and subtle than is generally acknowledged. In addition to the Orientalist influences, the French composer is prescient in his barbed, satiric treatment of British colonialism, with music for the supporting English characters centered on operetta frippery while that for Lakme and Nilankantha is deeper, richer and more eloquent.

Indeed, compared to, say Bizet’s Pearl Fishers, even with its faults, Lakme seems by far the richer, more musically varied and dramatically satisfying work. Still the opera remains more discussed than performed. FGO last mounted it in 1964, and the Met hasn’t touched Lakme since 1947 when Lily Pons sang the role on tour in Dallas.

For local favorite Partridge who is singing the role for the first time, the famous Act 2 aria is justly celebrated, yet it’s somewhat deceptive since nothing in the role is as stratospheric in the rest of the opera.

“From a coloratura standpoint, the Bell Song is challenging but it’s nothing out of the ordinary,” says Partridge. “Lakme really is a lyric part. The duets are long, and the voice you use to imitate a bell is not the voice you use later in the piece.”

There’s also a quirky abruptness to the writing, which gives it a natural, conversational feel. “I’m used to the long bel canto lines,” says Partridge. “”You don’t really get these arching lines in Lakme like you do in other lyric parts. You get a few but a lot of her recitative stuff is just five notes, then a rest, and six notes, then a rest. It makes her kind of diminutive and very delicate in a way.”

That quality extends to the finale which Puccini would have strung out for ten minutes but Delibes dispatches Lakme with French concision. “Everything dramatic happens so fast,” says Partridge. “She decides to kill herself and suddenly, she’s dead in like two pages of music! Maybe that’s what doesn’t resonate with a lot of audience members and why this piece isn’t done that much.”

Partridge studied the Joan Sutherland and Mady Mesple recordings, but these days tried not to be over-influenced by documents of the past. “When I was younger, I listened quite a bit and now I just try to be my own artist,” says the soprano. “I try to be scholarly but I also really want to express what’s happening in the music and the story.”

Florida Grand Opera’s Lakme opens Feb. 21 and runs through Feb 28 in Miami, playing March 5 and 7 at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts March 5 and 7. Leah Partridge and Bryan Griffin sing the roles of Lakme and Gerald Feb. 21, 24, 27 and March 5 with Evelyn Pollock and Chad A. Johnson in the roles Feb. 22, 25, 28 and March 7. $10 to $250. 1-800-741-1010; www.fgo.org.

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Sat Feb 14, 2009

at 7:27 pm

No Comments