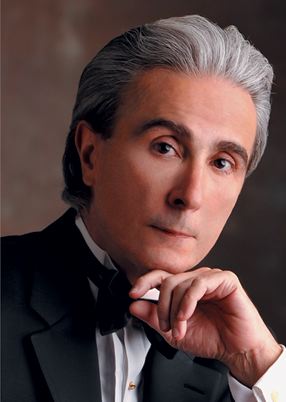

Pianist Rodriguez’s life and career come full circle at University of Miami

Santiago Rodriguez will perform music of Mozart, Schumann and Rachmaninoff Friday night as part of the Frost School of Music's Festival Miami.

When Santiago Rodriguez walks on stage at Gusman Concert Hall Friday night for a Festival Miami recital, the Cuban-born pianist will have come full circle on a journey that began when he arrived in Miami on a Pan Am propeller plane in 1960.

Inside the lining of the 8-year-old boy’s bathrobe were four hundred-dollar bills. His mother had sewn them in with a message to please use the money to continue his musical training.

One of thousands of children brought to the United States under the auspices of the Catholic Church as part of “Operation Pedro Pan” following Fidel Castro’s revolution, Rodriguez was first sent to a refugee camp in Kendall, then transported to the Madonna Manor Orphanage in New Orleans where he spent the next six years.

More than two decades later, Rodriguez is an acclaimed pianist who recently joined the keyboard faculty of the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music. He now looks forward to playing a vital role in the region’s concert and education life.

“Teaching is something I must do,” says Rodriguez, who is passionate about his role as an educator. “It requires true commitment, passion and the respect of your students.”

The pianist’s inspiration comes from his own distinguished teachers. When he was only four years old, Rodriguez began piano lessons with Nelson De Berge, who also taught him theory, solfege and sight reading.

“He opened up a whole new panoply of music,” Rodriguez recalled. “This was the best education, the best way to become a musician. Too many players wait too long to learn these things.”

After studying for four years, Rodriguez learned Mozart’s Concerto No. 27. Even though he did not speak English, he began studies with Charles Braswell at Loyola University. When he was fourteen years old, his teacher encouraged him to enter a young artists’ competition sponsored by the New Orleans Philharmonic Orchestra. Playing his Mozart concerto, Rodriguez won the contest and debuted with the orchestra at a youth concert, conducted by the ensemble’s then-music director Werner Torkanowsky. Impressed by the prodigious young pianist’s talent, Torkanowsky brought Rodriguez back annually.

“He gave me the gift of experience, like a musical father,” said the pianist. “I gave my first performances of three Beethoven concertos and works by Brahms and Prokofiev with Torkanowsky,” Rodriguez noted with nostalgia.

Rodriguez chose the University of Texas after visiting Austin and becoming entranced with the beauty of the campus. “Those were four of the happiest years of my life,” Rodriguez remembers. Studying with Professor William Race, a concert pianist who had performed widely across North America and Europe, was “most enlightening, learning to understand music in abstract terms.”

Intrigued by the “incredible sound and tone” of renowned pedagogue Adele Marcus, he pursued graduate studies at New York’s Juilliard School. Marcus encouraged Rodriguez to “develop your voice, make the piano sing.” He was so fascinated by that vocal analogy that he accompanied over twenty singers in the vocal studio of former Metropolitan Opera soprano Eleanor Steber.

After advancing to the finals of the 1976 Leventritt Competition, Rodriguez won a major management contract. The grand prize at the 1975 William Kapell Competition and Silver Medal at the 1981 Van Cliburn Competition catapulted him into the international spotlight.

Rodriguez is realistic about the role competitions can play in an artist’s career. “Competitions afford an artist without connections an entry into the music world but a competition winner cannot be considered a finished artist. Managers tend to over-expose many winners. Artists need to be allowed to grow. In Europe they nurture musicians. In order to be memorable, music speaks through the performer. A great work of art and the artist evolve.”

A meeting with legendary Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera at a recital at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (at which Rodriguez played Ginastera’s First Sonata) led to a twelve-concert tour with cellist Aurora Ginastera, the composer’s wife. Rodriguez treasures the memory of those performances and loves the intimate atmosphere and artistic interaction and rapport of playing chamber music. “Two years of trio concerts with violinist Ruggiero Ricci and cellist Nathaniel Rosen were my happiest time as a musician,” Rodriguez stated.

Ginastera requested that Rodriguez perform his second sonata, a work the pianist describes as “close to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring” in wild astringency and sheer difficulty. Rodriguez recorded a Ginastera album as the first release of Élan Recordings, a company founded by the pianist’s wife Natalia.

His sizable discography also includes rarely played concertos by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Carlos Surinach and the complete works of Rachmaninoff. He is particularly proud of his recorded version of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 with South Florida based conductor Paul Anthony McRae. An ambitious recording entrepreneur, Rodriguez has produced recordings of string quartets by Ginastera, Revueltas and Villa-Lobos (with the Cuartetto Latinoamericano) and the complete piano music of American composer Vincent Persichetti.

Rachmaninoff’s Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor and three preludes figure prominently on Rodriguez’s Festival Miami recital. His view of that iconic Russian pianist-composer’s music differs from the popular stereotype of post Tchaikovsky romanticism. “Rachmaninoff was a romantic personality but a very contemporary person. There is a dark world in his choral work The Bells and the Second Sonata, which is a strange, anxiety-ridden piece with elements of the macabre. Dissonance and chromaticism enrich small motifs that are embellished into melodies. The pianist must present Rachmaninoff’s inspiration at the tip rather than the Hollywood-end frosting.”

Rodriguez feels Schumann’s Carnaval, the other major work on his program “is always dark. There is external waltzing, a lot of dance macabre, minor key waltzes and interrupted dances. These are bizarre pieces that almost prefigure Schumann’s mental breakdown.” He would like to record Carnaval and looks forward to taping Schumann’s Fantasy and Granados’ Goyescas.

After taking a six-year break from concertizing, a few benefits apart, Rodriguez has returned to a modest touring schedule. On November 14 he plays a recital for the St. Martha’s concert series in Miami Shores, and Rodriguez joins violist Roberto Diaz and cellist Andres Diaz for a Friends of Chamber Music trio program on December 8.

But he insists he will never again play seventy-five to eighty concert dates a year. He emphatically quotes the legendary Italian pianist-composer Ferruccio Busoni: “Only perform when you have the absolute need to share music with someone.”

Santiago Rodriguez plays works by Mozart, Schumann and Rachmaninoff 8 p.m. Friday at Gusman Concert Hall. 305-284-4940; festivalmiami.com.

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Tue Oct 12, 2010

at 1:07 pm

No Comments