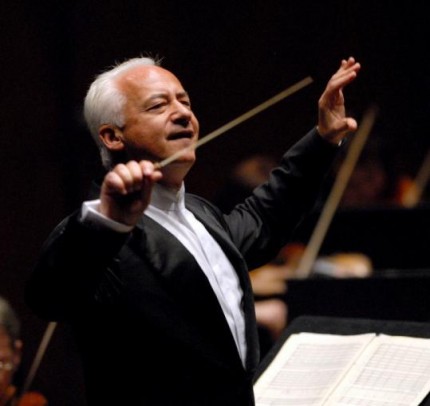

Spivakov, Moscow Virtuosi mark three challenging decades

Vladimir Spivakov and the Moscow Virtuosi will perform works of Boccherini, Mozart, Schinittle and Shostakovich Friday night at Symphony Center

The late Brezhnev era–a favorable period for the production of nuclear weapons, political arrests and wheat shortages–was not a particularly good time in the Soviet Union to found an unauthorized new chamber orchestra.

But it was in 1979, the year the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, that the highly regarded violinist Vladimir Spivakov founded the Moscow Virtuosi, an orchestra that would soon win acclaim for the brilliance and precision of its playing.

The story of the Moscow Virtuosi, which performs Nov. 24 at the Arsht Center in Miami, is one of musical excellence, official non-recognition and the mixed blessings of freedom–which in their case included violent robberies on the streets of Moscow.

Spivakov formed the orchestra in the midst of a promising career as a concert violinist, having won several competitions and embarked on international concert tours. But he acquired an interest in conducting, studying for several years in Moscow before going straight to the big leagues by making his podium debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at the Ravinia Festival.

Returning to the Soviet Union, he founded the Moscow Virtuosi by plucking first-chair players from leading orchestras, hiring competition winners and attracting members of a well-known string quartet. At first, the orchestra met in basements and shabby, out-of-the-way venues because as a non-official–and officially non-existent–orchestra, it couldn’t book major halls.

“It was three years underground,” said Spivakov, in a telephone interview from his home in Moscow. “I asked friends from different orchestras to get together and the minister of culture was against it, because I chose people myself. And for three years we have no state official recognition.”

But the ensemble’s reputation spread, and a 1981 review in Pravda led the Ministry of Culture to grant the orchestra official status. Recognition from the authorities brought mixed rewards. The ensemble received state support and the opportunity to play in leading concert halls. It also received a clunky Soviet name, The Moscow Virtuosi State Chamber Orchestra, and orders to perform mediocre contemporary composers favored by the authorities (“You don’t know these names,” Spivakov said. “I tell you, but you wouldn’t know.”) and avoid composers that made them nervous. “It was difficult to play Schnittke because it’s spiritual work, or Arvo Pärt,” he said.

With glasnost, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the orchestra acquired the freedom for which Spivakov had yearned. And it acquired all the problems that came with it. “Now it’s difficult because we have no state support like before,” he said. “We’re much more free. We can play what we want. We can go where we want. It’s not easy.”

In the winter of 2008 two of the orchestra’s violinists were robbed in separate, violent incidents on the streets of Moscow, leading to speculation that a rival orchestra was behind the attacks. But it turned out that one attack was the responsibility of two unemployed Siberians who thought there might have been something to eat in the musician’s violin case. Finding no food, they ditched the $35,000 instrument in some bushes. The other robbery, Spivakov said, had been a hate crime. “We still have some nationalistic groups,” he said. “And one man who has a Korean face, he was attacked. But he’s a Russian Korean. He doesn’t speak Korean he just looks Korean.”

Today the orchestra tours and records extensively. The orchestra has never placed a premium on sensitivity to historical styles, and some listeners hear a throaty late-romantic Russian approach applied freely to Baroque and Classical works. But there’s general agreement among critics on the ensemble’s precision, style and panache.

The musicians of the Moscow Virtuosi take the title of their ensemble seriously, regarding themselves not as a collection of replaceable instrumental parts but as a group of individual virtuosi. Unlike symphony orchestras, where auditions focus largely on excerpts from difficult orchestral works by Strauss, Wagner and so on, Spivakov said violinists seeking to join the Moscow Virtuosi are expected to play only virtuoso works by such composers as Paganini, Ravel, Sarasate and Saint-Saëns–brilliant, finger-busting solo compositions that swiftly reveal a violinist’s level of technique.

But beyond technical ability, the orchestra looks for musicians who can fit into the orchestra’s musical culture, a collegial environment in which everyone is expected to take an interest in what everyone else is playing. “We try to find people who are not only professional but good people, with positive dispositions, joyful and who not only work for money, [but instead] who work for music,” said Aleksey Lundin, the orchestra’s concertmaster. “It’s very important, for us and for Vladimir Spivakov also. If we like somebody we try him in some concerts and some rehearsals. If he’s good, we like him in our orchestra.”

During rehearsals, the atmosphere differs from that of a symphony orchestra, which function as top-down organizations under the rigid control of the conductor. “It’s like a quartet, not like in an orchestra where the conductor shows something and everybody just looks at his hand with no ideas, no opinions, just do what he wants,” Lundin said. “In our orchestra we are like in a quartet, like a big family. Everybody knows all the music, each part. The violinists know what the double basses are playing and what they are bowing at the same moment.”

The young Russian pianist Olga Kern, who has toured with the orchestra, said the musicians achieve a unique level of unity and musical power. ” They’re incredible musicians,” she said. “They sound like one big instrument. Spivakov is such a great violinist himself. He just makes the orchestra sound like his own violin. The orchestra it’s not just an accompanist. There’s a reason they’re called the Moscow Virtuosi.”

The Moscow Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra performs 8 p.m. Nov. 24 at the Arsht Center in Miami. The program includes Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto in E minor, Rossini’s Sonata No. 3 in C major, Boccherini’s Symphony No. 4, Casa del Diavolo, and Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings. arshtcenter.org; 305-949-6722.

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Wed Nov 17, 2010

at 3:24 pm

No Comments