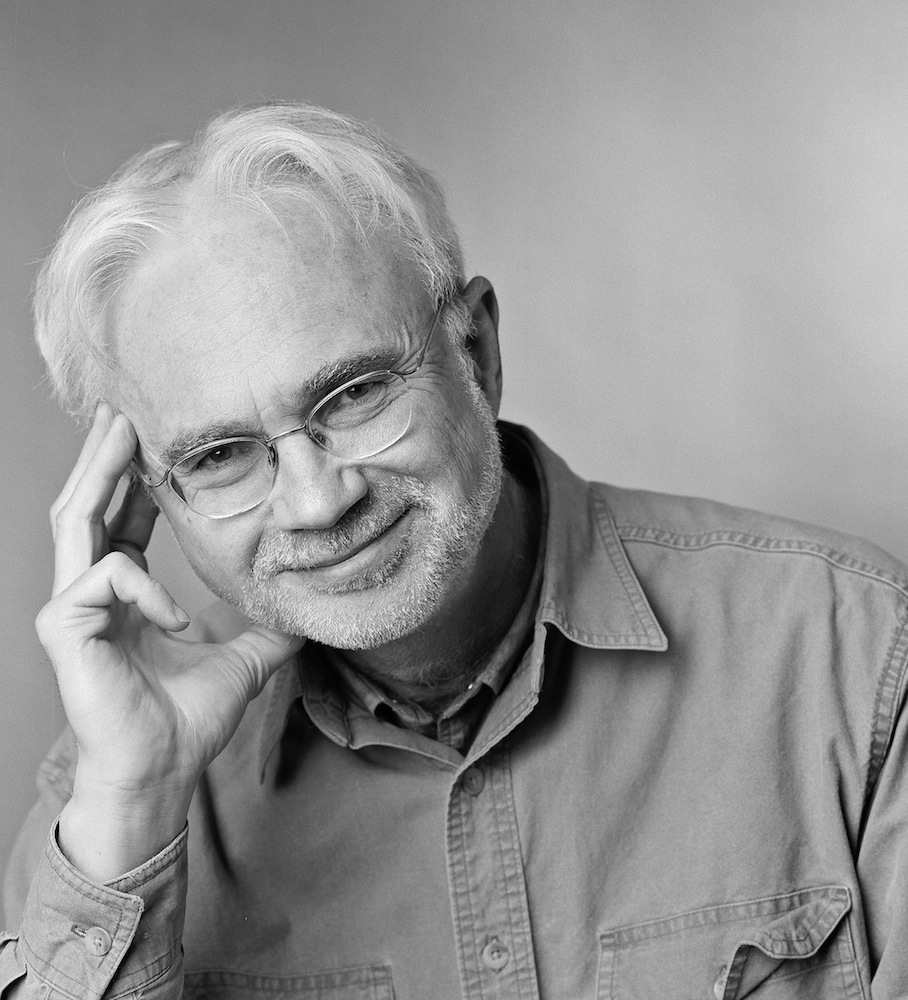

En route with a package, John Adams reflects on the Met, film noir and young musicians

John Adams will conduct the New World Symphony Saturday night in a program that contains the regional premiere of his "City Noir."

John Adams has just finished writing another symphony. At least, he thinks it’s finished. Last Friday, he went for a second opinion.

The American composer, who lives in Berkeley, drove across the Golden Gate Bridge that morning to hand deliver the manuscript of Absolute Jest to his friend, conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, who will premiere the work next March 15 during the San Francisco Symphony’s centennial season.

“We’ll see what he says,” Adams ventures during a commuter phone conversation conducted between his house and Tilson Thomas’ office.

There is less mystery around this weekend’s collaboration. Adams returns to Miami Beach on Saturday to conduct the New World Symphony, the post-graduate orchestral academy founded by Tilson Thomas.

It will be Adams’ first time at the symphony’s South Beach micro-campus, designed by architect Frank Gehry, and his first turn at the podium in the New World Center’s 756-seat concert hall.

He is not taking the new room for granted, any more than he’s taking positive feedback for Absolute Jest on faith.

Such a wait-and-see posture does not spring from his résume. Adams has a Pulitzer Prize, for his 9/11 elegy On the Transmigration of Souls. His works are thriving in symphony halls. He is fresh off the triumphant Metropolitan Opera premiere of Nixon In China, the tragicomic tour de force — Air Force One and all — which Adams himself conducted at New York’s Lincoln Center in February.

It’s just that Adams — whether discussing new material, the Nixon revival or his weekend concert here — is a man who seems to pay far more attention to process than accolades for his accomplishments.

Before acknowledging that he was “very happy” with his Metropolitan Opera experience, he talked about the effort involved.

“Everything at the Met is grand, including the distances,” Adams said. “So it was a challenge to get everything tight.” He means physical distance in some sense — Lincoln Center is vast above and below ground — but more the logistical and psychic distance between rehearsals and opening.

In Miami Beach, Adams will lead the New World musicians in a performance of his 2009 symphony, City Noir. He has been thinking ahead about how to adapt the music, written for a large orchestra, to more intimate surroundings.

“City Noir is a big piece,” Adams says, “big in scope, big in forces.”

The work premiered at another Gehry sonic temple, the 2,265-seat Disney Hall in Los Angeles, and, as its title suggests, City Noir will challenge the New World players to navigate an asphalt jungle of sound. Adams said he wrote the symphony as an imagined score for noir movies and the mid-century milieu they conjured in black and white.

Think of it as a polyphonic L.A. Confidential.

“There is a wonderful sensibility that many of them share,” he says. “The dark side of American urban life, the potential violence, the jagged edge between extreme lyricism and violence and the sort of jazzy undertone.”

He also wrote his own figurative soundtrack, largely as a film noir fan, since he is ambivalent about the use of music in movies.

“You start with something that promises to be a great experience of the combination of imagery and music, and then the music stops,” he said.

And that’s assuming the work even belongs in the finished product. “Most film directors have pretty bad taste in music,” Adams said. “And when they use classical music it’s usually a terrible choice.”

Adams makes two exceptions: Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, for Lux Aeterna and Atmospheres by Ligeti; and David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, for the song Im Abdendrot by Richard Strauss.

The composer has equally mixed feelings about how his own music has fared in film. Last year’s I Am Love starred Tilda Swinton as a Russian exile with a wealthy Italian husband, three grown children and a luxurious villa in Milan, and was set to preexisting Adams recordings. “Some of it was really good,” he said. “I had some issues with the ending.”

In that film Adams’ clanging Harmonielehre plays through a final reel that Adams aptly described as “an extreme moment of liberation” from a suffocating relationship that Swinton’s character has “given up everything to achieve.”

“I found it a little bit of an uncomfortable marriage,” he said of the closing sequence and his music. “But that may just be because I had my own personal scenario for the ending of Harmonielehre. … I may not be the best person to ask.”

Adams is no stranger to the vernacular. His blog, “Hell Mouth,” shares its name with the demon gate of television’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer. And while his methods are classical, Adams’ aesthetic is restlessly contemporary (which is not to say pop). His subject matter in seminal works — from Nixon and Transmigration to Doctor Atomic (2005) and The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) — falls somewhere between history and news cycle.

The New World program anchored by City Noir also features Béla Bartók’s Dance Suite and Adams’ first run at a work by New York-based contemporary composer Julia Wolfe. Adams will conduct Wolfe’s Arsenal of Democracy (1993), a surging chamber piece written as a reflection on American political speech.

After that, he’ll tend to Absolute Jest and assorted other projects. As busy and engaged as he is, one can hear him pausing for reflection — as in his stated happiness to be working with younger musicians. “Some of it has to do with age,” he said. “I’m 64 now.”

He has two children of his own, both in their 20s. His son Sam actually intersected with Julia Wolfe’s music before his father, conducting Wolfe’s six-piano flourish, My Lips from Speaking, at a performance in New York.

“So I’ve watched this particular generation grow up very carefully,” Adams said. “It’s just amazing not only the way they play, but their comfort with the contemporary repertoire.”

The classical world has likewise come around to the iconoclast Adams, who has known his share of controversy from the Nixon in China premiere to Klinghoffer, a work that initially outraged some supporters of Israel.

His 2008 autobiography, Hallelujah Junction, won glowing reviews. He’s now had two operas, Nixon in China and Doctor Atomic, presented at the Met — the heart of opera world establishment — in the last three years. As his accomplishments go, the Met’s embrace is one he said he almost finds hard to believe.

So is he in the regular standard repertoire now, right next to Bach and Puccini?

“The younger composers probably won’t speak to me anymore,” he joked. “When I was in my 20s, I hated the thought of some successful composer in his 60s. … I’ll try to keep my membership card in the younger generation.”

John Adams conducts the New World Symphony, 7:30 p.m. Saturday at the New World Center, 500 17th St., Miami Beach, 305-673-3331, 800-597-3331, nws.edu. The performance is sold out.

Posted in Articles

2 Responses to “En route with a package, John Adams reflects on the Met, film noir and young musicians”

Leave a Comment

Wed Mar 30, 2011

at 10:05 am

2 Comments

Posted Mar 30, 2011 at 3:52 pm by Justin Moss

Very nice interview and article! I bet, though, that if Adams was driving from his home in Berkeley to deliver a score to Mo. Tilson Thomas in San Francisco, he took the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge rather than the Golden Gate.

Posted Apr 10, 2011 at 7:40 am by Sean Piccoli

Justin, hi, and thank you the catch. I am debating tracking JA down again to cinch the correction because that’s one of those factual bobbles that drives me crazy. I could have sworn it was the GG but my notes are fuzzy on this point. It’s possible he just said “the bridge” and I showed my non-resident status by assuming the one tourists know. S.