Miró Quartet’s edgy style brings illumination in Barber and Beethoven

The Miro Quartet performed music of Beethoven, Barber and Dvorak Sunday at Gusman Concert Hall.

When founders of a string quartet name their ensemble after a surrealist painter who hated conventional art, they are telling the world not to expect the usual sounds of the chamber music salon.

The Miró String Quartet, which performed Sunday at the University of Miami’s Gusman Hall, lived up to its name in a concert that went deeply into the works on the program, with sounds that weren’t always pretty but were thought out, authoritative and technically almost flawless.

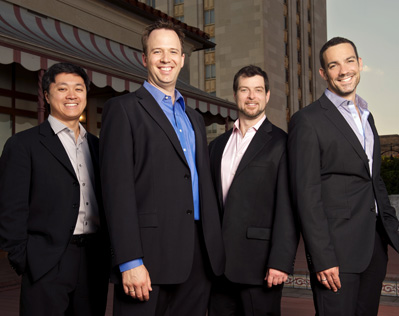

Founded in 1995 at the Oberlin Conservatory, the quartet quickly won several prizes and went on to become one of the world’s leading chamber ensembles. Named for the Spanish painter and sculptor Joan Miró, the quartet has a distinctive style, more bumptious and astringent than the rich, refined sound produced by the top quartets of the previous generation. This was for no lack of technical ability, as the musicians achieved a high standard of intonation and precision, with a natural ensemble cohesion that came from paying close attention to each other’s playing.

The concert, presented by Sunday Afternoons of Music, opened with Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 2, Op. 18, one of the most classical in tone of his early quartets. Performances of Beethoven’s first set of quartets often look ahead toward the composer he would become, and this performance fell decisively into that category. The Miró players favored clipped, abrupt endings to phrases, sudden shifts of mood, and sharp changes in dynamics. They didn’t put anything in that wasn’t already there, but they tended to maximize every contrast in volume or mood, for a performance that injected a bracing jolt of energy into this otherwise polite work.

In the opening movement, first violinist Daniel Ching played in an assertive manner that recalled Beethoven’s time, when these works were known as “violin quartets” and the other players were merely accompanists. In the final movement, they emphasized the sudden drama that emerges in a dark melody in the first violin and cello, putting extra bite into their playing.

An old string quartet joke (they do exist) says a string quartet consists of a good violinist, a bad violinist, an ex-violinist, and someone who doesn’t even like the violin. The ‘bad violinist’ in the Miró would presumably be second violinist William Fedkenheuer, who just became the quartet’s newest member. But Fedkenheuer was a particular standout in this performance, especially in the first and fourth movements of the Beethoven, where his big tone, authoritative style and rock-solid technique made him the full equal of Ching.

Their style of performance more naturally suited the next work on the program, the American composer Samuel Barber’s String Quartet, an early work that was his only attempt at the form. The bracing opening, the songlike melodies and the mysterious quiet passage before the return of the theme all came off with conviction in their hands.

The quartet is best-known for its famous Adagio, which in the composer’s arrangement for string orchestra became familiar to scores of people through various film soundtracks. The Adagio seemed to begin too prettily, with the musicians ladling a throbbing vibrato on the theme that left it no place to go as the coming passages called for more intensity. As the movement built to its climax, cellist Joshua Gindele and violist John Largess revealed, warm, noble tones, and the agonized climax was a searing, almost violent passage without a trace of the throbbing romanticism that opened the movement.

The Quartet No. 12 by Dvořák, known as the American quartet, took up the second half. Violist Largess played the opening theme with a clear, muscular tone. The quartet brought crisp textures and a straightforward approach to the the big, wide-open canvas of this work. In the fourth movement, first violinist Ching had the main theme, but a lot of the musical interest was in the busy, running accompaniment, and Ching never overpowered it.

That the quartet can produce sounds as sumptuous as any was clear from the encore, the Cavatina from Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 13, one of the most accessible and appealing movements of his late quartets. Their prior bumpiness and astringency vanished for this movement, played in a hushed, almost reverent manner, and they displayed considerable aplomb in carrying on when a fire alarm went off a few minutes into the movement.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Mon Feb 13, 2012

at 12:04 pm

No Comments