MTT, New World to close season with Mahler’s Ninth

Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 9 will be performed this weekend by Michael Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony to close the orchestra's season.

When Michael Tilson Thomas raises his baton Saturday evening to lead the New World Symphony in a performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, it will be 100 years — almost to the day — since the premiere of that work in Vienna.

Mahler died before he could hear his final symphony performed in June of 1912. But he had predicted his time would come, when the world would understand and appreciate the vast, intimate, searching, terrifying and grandiose symphonies he composed during summers off from his job as a conductor.

Today he is considered one of the world’s greatest composers, an artist shaped in the capitol of the diverse and decaying Austro-Hungarian Empire, composing his symphonies as Freud, electricity and telephones allowed the modern age to gloomily dawn, whose work, for some, speaks to contemporary audiences with an immediacy that even composers such as Bach and Mozart, great as they are, cannot.

“We probably recognize the kinds of conflicts, the kinds of ambivalence and ambiguity, of which his music so often speaks and we’re perhaps more aware of the complex inner lives we lead,” Tilson Thomas said. “That’s a lot of what his music is about, and that was very disturbing to many people when it was first written because they felt that his music was shattering their comfort zone in their relationship to music, they thought music should be a kind of comfortable, predictable sort of refuge, as opposed to a place in which ideas both elevating and disturbing were being presented.”

Tilson Thomas first heard Mahler at the age of 12, when someone gave him a record of the First Symphony. He liked it but wasn’t enamored of it. “But then shortly thereafter, by accident I heard the last movement of Das Lied von der Erde, and that just floored me,” he said, referring to the huge late vocal and symphonic work that Mahler composed before the Ninth Symphony. “I just was completely stunned with the music, the range of expression, and how closely the music seemed to express all sorts of feelings that I was just discovering that I had, and from then on it became an essential part of my life.”

At the age of 24, in his first Mahler performance, he led the Boston Symphony in the Ninth Symphony. Of Tilson Thomas’s ten Grammy awards, six were received for his complete Mahler cycle with the San Francisco Symphony.

His end-of-season Mahler performances with the New World Symphony, which will continue next year with the Fourth Symphony, have become highlights of the year, giving South Florida audiences the chance to hear intense, focused performances by one of the world’s leading living Mahler interpreters. Although both Saturday evening and Sunday afternoon performances are likely to sell out, the Saturday concert will be projected live on the hall’s viewing wall, allowing anyone in the adjacent park to watch and listen for free.

Like most of Mahler’s symphonies, the Ninth is one of the longest works in the repertoire, lasting around 85 minutes. For this weekend’s concerts, no other work will be on the program. The first movement, which is itself longer than the entire Beethoven Eighth Symphony, shifts between gentle, lullaby-like melodies and grimly dramatic sections before fading out. The two inner movements are fast, raucous affairs, the first rustic, the next demonic. The last is a long slow movement, an elegiac valedictory. Nothing quite sounds like the Ninth Symphony, a work that contains orchestral passages as lush as anything in Dvorak, wispy passages for odd, chamber-like combinations of instruments, harsh brass tones and moments of high drama.

“It’s a Romantic symphony on the edge of the 20th century,” said James Zychowicz, a musicologist and Mahler scholar who recently led a seminar on the Ninth Symphony at Juilliard. “It’s a work that sounds familiar, and yet it takes us in new directions. We’ve got this full orchestra that’s amazing, the sheer sound is overwhelming. Yet we’ve got chamber-music like sounds that are so intimate that we have to almost listen more carefully. It forces us to lean forward in our seats almost. In a way he’s commanding the audience to listen.”

“The first movement of the Ninth Symphony is his longest symphonic movement,” he said. “It certainly is one of the more challenging ones structurally. In live performances, I see audiences just enraptured. They’re following it aurally, the amount of ambient noise I hear is minimal, as if they’re all holding their breath until the end.”

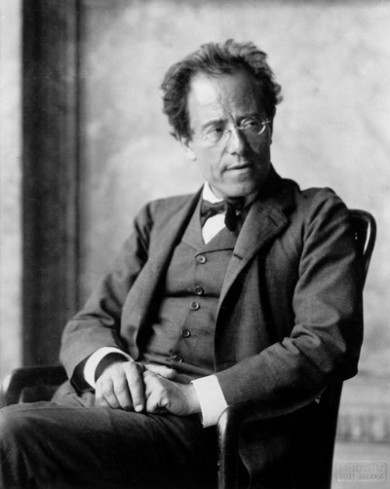

Michael Tilson Thomas

Tilson Thomas has been quoted calling the Ninth his favorite of the Mahler symphonies. Asked if this was still true, he hesitated. “I guess,” he said. “I’ve had very affectionate feelings for them all, but what I like about the Ninth is that it returns to the expressive territory of the early symphonies, the really enchanted, sort of childlike aspects of the early symphonies. But now it goes back to that with so much greater perspective, so much greater depth, so many other possibilities.”

A man as conscious as Mahler was of the reality of death was not unaware of what’s been called the curse of the ninth symphony, which claimed Beethoven, Schubert, Dvorak and Bruckner, all of whom composed nine symphonies and didn’t live to write a tenth. The conductor Leonard Bernstein has suggested the fluttery rhythm heard throughout the first movement of the Ninth was Mahler’s portrayal of the heart ailment with which he had recently been diagnosed. And through the course of the symphony, particularly the long, slow last movement, with its aching suspensions and cadences that seem unwilling to let go, many listeners have heard Mahler’s long farewell to life. While experts say it’s clear Mahler could hear the footsteps of the Reaper, he’d heard them his whole life, and a nagging awareness of his own mortality does not distinguish him from composers as diverse as Mozart, Brahms and Wagner.

“A lot of program notes and liner notes describe the Ninth as being all about death, that it’s all about a farewell to life,” said Katarina Markovic, chair of the music history and musicology department of the New England Conservatory of Music and a Mahler scholar who helped lead a festival of the composer’s work last year. “And obviously there is something to it, but at the same time another paradox is that if you look at the documents — we have letters, as well as reminiscences of his friends that visited him during the composition of the Ninth symphony – what we get is a story that’s completely different. We see a Mahler who writes that he’s more enthusiastic about life than ever. He writes especially to Bruno Walter, who premiered the symphony two years later, I feel so much alive, I am thirstier for life than ever.”

Adds Zychowicz, who recently examined a manuscript of the symphony at The Morgan Library in New York, “The handwriting is amazing. It’s not someone who’s writing his last will and testament. It has changes, scratches out, of someone who’s really engaged in writing, and it’s someone who really wants to get his ideas down precisely. It’s an exciting manuscript.”

It is these contrasts, the unresolved grappling with the complexities of life and the universe, that helps account for why Mahler speaks to us today. “Mahler has this openness to the variety of different human experiences that is characteristic of our time,” Markovic said. “He approaches a fractured, diverse modern world that, because of his own experiences, he somehow had to deal with. That is something that echoes with us and with our experiences, with our society, there are so many issues of multiple religions, multiple spiritualities coexisting. There’s an acceptance of the variety and diversity of life in Mahler. That’s what makes him a very modern, 21st century man.”

The New World Symphony performs Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 at 8 p.m. Saturday and 2 p.m. Sunday at New World Center in Miami Beach. The Saturday performance will be projected live on the hall’s viewing wall facing the adjacent park. nws.edu, 305.673.3331

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Wed May 2, 2012

at 10:53 am

No Comments