Violinist Ray Chen brings more fire than finesse to Sunday Afternoons program

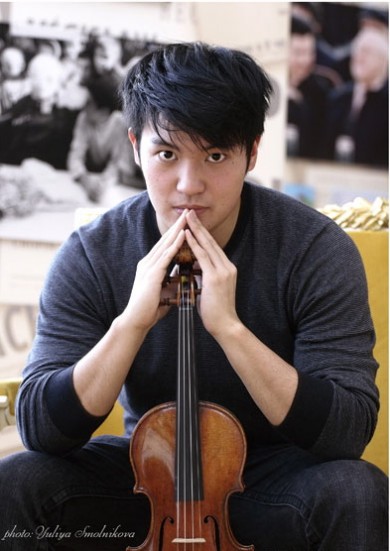

The flashy young violinist Ray Chen came to the Sunday Afternoons of Music Series in Coral Gables for a concert that turned out to be unexpectedly fraught with significance.

Doreen Marx and Byron Krulewitch, the married couple who have managed the series for 33 years, had announced earlier that week that they would stop running it at the end of this season. Many members of the audience at the University of Miami’s Gusman Hall were aware of the news, and as soon as Marx walked in, she was greeted by a burst of applause.

Marx, not normally at a loss for words, was so concerned about getting it right that she read from a prepared statement.

“It has been an honor and a privilege to bring music to you for 33 years,” she said. “Byron and I are thrilled that we have been able to bring world-renowned musicians to our patrons, sponsors and ticket-holders.

“If we have enriched all of you with music in heart and soul, then our work has been worthwhile. If a child appreciates a classical concert and supports the arts down the road, then out work will have been worthwhile If we have created an emotional moment through the arts, then we will know that our work has reached you.”

Then it was on to the recital. Chen, who was accompanied by the fine pianist Julio Elizalde, has a brilliant technique and a big, rich tone. Not every piece of music on the program demanded all that heavy bow pressure and throbbing vibrato, however, and sometimes he needed to vary his style more than he did.

They opened with Mozart’s Violin Sonata in A Major, K. 305. The first movement zipped along with the fizzy momentum of a Mozart overture. Elizalde played assertively but Chen matched him. The second movement, a theme and variations, with a quick final variation that served as a sort of last movement, was less successful. Mozart’s delicate melodies needed more grace and less heavy, grainy bowing.

Next came three works by the 19th century Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who set the standard for the sort of dashing virtuosity that is Chen’s strong suit. In Habanera, a smoky, atmospheric work, Chen effortlessly handled all the fearsome technical difficulties that decorated the melody—-runs of two simultaneous notes, artificial harmonics, rapid passages to the instrument’s topmost notes. The Sarasate work that followed, Playera, was all smoky melody and no virtuosity, which showed, unfortunately, how dull this music could be without the fireworks.

Next came Sarasate’s most famous work, Zigeunerweisen, or Gypsy Airs, a work that packs an amazing amount of soulful melody, hot-blooded passion and bravura technical display into a few minutes of music. Chen launched into the opening melody with a fierce, throaty manner and brilliantly played the runs that swarm around the tune. One might have wanted a bit more pathos in the melodies, yet the high-speed finale was a showstopper, with Chen playing the violin about as fast as it could be played.

Beethoven’s Sonata No. 9, known as the “Kreutzer,” is the longest and grandest of his ten sonatas for violin and piano. Chen gave a majestic account of the rolling chords for solo violin that open the work. He and Elizalde plunged into the ensuing Presto movement at high speed, but with such crispness, force and rhythmic bite that the performance never became a blur and effectively expressed the grim drive of Beethoven’s music.

In the second movement, Elizalde played with the sort of effortless elegance that seemed to fit this theme and variations. Chen was again too heavy and aggressive at points where the music needed more finesse. In the final movement, another headlong rush of notes, the two musicians displayed the same virtuoso control at high speed and brought the sonata to a forceful, compelling close.

As an encore, they gave an emotional account of the Meditation from the opera Thaïs by Massenet, dedicating the performance to Doreen Marx and Byron Krulewitch.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Mon Feb 17, 2014

at 11:43 am

No Comments