FIU presents an ambitious if uneven staging of Weill’s” Street Scene”

In the years following World War II, many composers felt the path to the Great American Opera was through the Broadway theater. The early works of Gian Carlo Menotti were produced commercially on Broadway and there seemed to be a moment when fusion of classical and populist music theater genres was a possibility.

Kurt Weill’s Street Scene is a product of that heady era. While the initial production had a short run, the work has been revived with some frequency by American and European opera companies. On Saturday night the FIU Opera Theater opened a two-day run of the 1947 opera at Florida International University’s Wertheim Auditorium, the most ambitious production to date for the school’s vocal department.

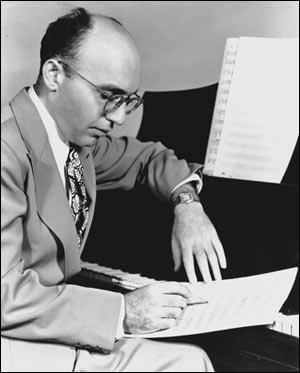

Weill first achieved fame for his German collaborations with playwright Berthold Brecht (The Threepenny Oppera, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny). Reflecting the cynicism of the social milieu of the Weimar era, Weill’s scores mixed the jazz-influenced aura of 1920’s cabaret with the atonal sounds of Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School. Emigrating to United States after the Nazis came to power, Weill forged a new, distinctively American musical identity. He was immediately drawn to the musical theater. Working with some of New York’s best lyricists, he created a string of hit musicals featuring such great standards as September Song, Speak Low and My Ship. Still, Weill wanted to move the American musical toward a more ambitious, larger scaled vision of music drama.

Choosing Elmer Rice’s 1929 tenement play Street Scene, Weill produced a terrific score that finds the verismo of Mascagni sharing space with the song and dance world of Richard Rodgers and Cole Porter, even throwing in a jitterbug number and a touch of modernist dissonance. Weill’s juxtaposition of genres is masterful as when an anguished wife’s lament is followed by a septet saluting ice cream or a vaudeville routine precedes the murder scene.

While Rice’s drama now seems simplistic and loaded with ethnic stereotypes, the opera’s libretto by Langston Hughes, the great poet of the Harlem Renaissance, is alternatively moving, witty and sarcastic. The tale of unlikely lovers, an unhappy marriage ending in adultery and murder amidst an impoverished New York neighborhood is tailormade for operatic treatment.

All credit to director Robert B. Dundas for staging this American gem and for creating an inventive, yet intimately scaled production. Amanda Sparhawk’s street setting around the multi-level tenement building allowed the protagonists’ confrontations to take center stage. Regina Vellanti’s swift moving choreography made the most of limited stage space.

Conductor Grezgorz Nowak was the evening’s true hero. Well-versed in Brahms and Schumann, Nowak proved totally idiomatic in Weill’s blend of vernacular lyricism and 1940’s pop music. The playing of the student orchestra was bright and smooth, the strings silky and brass and percussion swinging and characterful. Indeed one could hardly believe this was a student ensemble.

The Wertheim does not have an orchestra pit, the improvised space leaving the musicians on the same seating level as the audience. This created serious balance problems. Weill’s instrumental scoring is thick and the talented cast was often swamped by the orchestral sonority, making much of the text indistinct. Discreet use of amplification would have aided the singers’ articulation and allowed for less stress on the youthful voices.

Despite these problems Sarah Payne emerged triumphant as the ill-fated Anna Maurrant. An expressive dramatic soprano with a powerful upper register, Payne’s diction was impeccable, the text clear and given strong dramatic inflection. In the aria Somehow I Could Never Believe, she encapsulated Anna’s mood swings from early daydreams of love to despair of her hapless existence. As her husband Frank, Darren Littman was appropriately rough-hewn, his burly baritone not always firmly focused.

The Maurrants’ daughter Rose sings What Good Would the Moon Be, one of Weill’s most memorable melodies. Evelyn Saavedra, the star of last year’s production of Handel’s Agrippina, was less effective in this ingénue role. While her timbre is attractive, Saavedra struggled with her upper register. She was most effective in her scenes with Scott Tripp as Sam Kaplan, a law student who is strongly attracted to Rose. Their duets exuded youthful ardor even when the text was unclear. Tripp sounded undernourished in the plaintive Lonely House but gained strength, rising to eloquent declamation in the impressively staged ensemble following the murder.

The cameo role of Harry Easter, Rose’s coworker and suitor, can stop the show with Wouldn’t You Like to Be on Broadway, an old fashioned Tin Pan Alley tune, but Juan Mansilla was a cipher, vocally weak and lacking charm. Edgar Abreu made the most of Lippo Fiorentino’s scenes, singing and dancing with abandon. Daniel Rodriguez turned Sam’s socialist philosopher father into the drama’s conscience in a fine acting turn.

Street Scene is a significant work. Perhaps Florida Grand Opera, with its new emphasis on American scores, can mount a full-scale production that will do justice to Weill’s vision. The hard-working FIU cast deserves credit for a fine effort.

FIU Opera Theater repeats Street Scene 3 p.m. Sunday at Wertheim Auditorium in Miami. 305-348-0496; music.fiu.edu.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Sun Mar 2, 2014

at 12:36 pm

No Comments