Over a tumultuous 75 years, Florida Grand Opera has seen its share of highs and lows

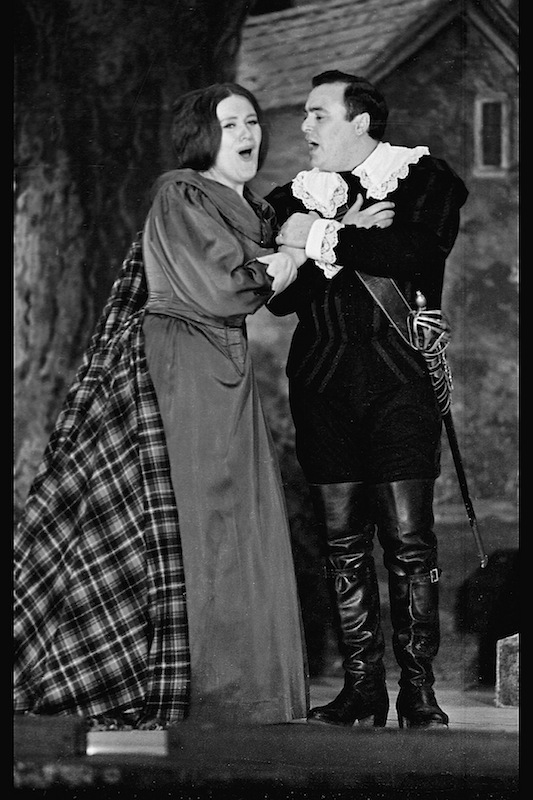

Luciano Pavarotti made his American debut in Miami in 1965 with Joan Sutherland in Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor.”

On February 15, 1965, a young Italian tenor made his American opera debut in Miami opposite Joan Sutherland in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. His name was Luciano Pavarotti.

In December of 1987 music critics from around the world converged on Miami for the American premiere of Rossini’s Bianca e Falliero, presented by Florida Grand Opera.

On January 14, 2004 Szulamit by Ede Donath was exhumed at Miami-Dade County Auditorium, marking a low point in FGO’s fortunes.

And in November, 2013, a new era was launched with the Florida premiere of Mourning Becomes Electra by longtime Fort Lauderdale resident Marvin David Levy, the first production presented by new CEO Susan Danis. That compelling production seemed to usher in a new era of optimism and adventurousness in a company that had too often seemed mired in mediocrity and dull repetition of standard repertoire.

Those four examples represent the long artistic journey and history of a company that has seen its share of triumphs and failures, at times presenting opera at its highest level as well as productions that were near-total embarrassments.

When the curtain goes up on Rossini’s Barber of Seville Saturday night at the Adrienne Arsht Center, Florida Grand Opera will launch its 75th anniversary season at a crucial moment in its history—as the company continues to struggle with financial problems while trying to maintain high artistic standards and remain culturally relevant and innovative in a difficult market.

__________

Opera in Miami began with the vision of Arturo Di Filippi, a tenor and voice teacher at the University of Miami. Forming the Opera Guild of Greater Miami in 1941, Di Filippi staged his first production the following year—a single performance of Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci at Miami Senior High School.

Rechristened as Greater Miami Opera, Dr. Di, as he was affectionately called, moved his productions to the new Dade County Auditorium. Producing mostly standard Italian and French repertoire, Di Filippi’s seasons featured such operatic luminaries as Richard Tucker, Renata Tebaldi and Franco Corelli as well as Pavarotti’s debut.

While he maintained high musical standards, Di Filippi paid little attention to theatrical values. He continually employed Anthony Stivanello, known as “Mr. Instant Opera.” With a large warehouse of all-purpose costumes and painted paper and cardboard backdrops, Stivanello serviced many regional companies in the 1950’s and 60’s. His productions were highly provincial, with staging consisting merely of blocking and stock gestures.

During the summer of 1972, Di Filippi died unexpectedly. He had already planned the following season which went on as scheduled. The April 1973 performance of Verdi’s Il Trovatore seemed to sum up the Di Filippi era. The production was rudimentary, the staging unsubtle but the night was filled with thrilling, world-class singing from Monserrat Caballé, Bernabe Martí, Lili Chookasian and Matteo Managuerra.

The organization’s board eventually appointed Robert Herman as director. Herman had been an assistant manager of New York’s Metropolitan Opera. With his Met connections, Herman was able to bring the world’s top singers to Miami. His productions were strongly cast and well rehearsed. The era of instant opera was over. Herman phased out Stivanello, importing productions from major houses (including the Met) and eventually commissioning new stagings.

In 1975 Herman presented The Flying Dutchman, Miami’s first Wagner opera. For this ambitious offering, he brought the veteran Met team of director Nathaniel Merrill and designer Robert O’Hearn as well as the experienced German opera conductor Reinhard Peters. The austere staging and the superb Wagnerian voices of Norman Bailey, Teresa Kubiak, Sandor Konya and Giorgio Tozzi would have been welcome at the Met or Bayreuth.

That boldly innovative Dutchman, however, was a one-off event and not indicative of Herman’s repertoire and theatrical predilections. He was highly conservative, continually programming standard Italian repertoire in frequently opulent productions. In 1976 a grandiose Otello brought Jon Vickers’s towering portrayal of Verdi and Shakespeare’s Moor, sharing the stage with Teresa Zylis-Gara and Peter Glossop. Placido Domingo starred memorably in Giordano’s Andrea Chenier. In his artistic prime, Domingo brought golden-toned vocalism to the title role of the French revolutionary poet. Pavarotti returned for L’Elisir d’Amore, La Boheme (with Mirella Freni), Tosca and Un Ballo en Maschera.

FGO presented the U.S. premiere of Rossini’s “Bianca e Falliero” in 1987 with Gianna Rolandi and Kathleen Kuhlmann.

Herman also made some artistic missteps. Cesare Siepi’s diminished vocal resources were not up to the demands of the protagonist of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Boito’s Mefistofele and Montemezzi’s L’Amor dei Tre Rei, both works by second-rate composers, were among his few choices outside opera’s Top 20 hits. Herman had an aversion for Mozart’s operas, publicly declaring that he found them too long and boring. His English-language version of Abduction from the Seraglio was poorly sung and clumsily staged.

Herman seemed to be running out of steam in his later seasons. He retired in 1985 and Robert Heuer, who had been assistant manager for several years, was anointed his successor.

At first the Heuer regime seemed like a breath of fresh air. The neglected Mozart repertoire became a company staple. Herman had appointed native Miamian Willie Anthony Waters to succeed Emerson Buckley as artistic director. Waters led an intense reading of Mozart’s opera seria Idomeneo, a sizzling Salome, Miami’s first Strauss opera, and a lyrical Die Walkure (with James Morris as Wotan) Waters’ leadership of more familiar works proved less effective.

Heuer also gave attention to American opera, starting with an excellent production of Carlisle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men, directed by the composer. Stephen Paulus’ searing operatic version of James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice was presented in a striking production by Broadway director Gerald Freedman that shocked some audience members with its sexual explicitness.

Perhaps Heuer’s major achievement was the American premiere of Bianca e Falliero, a Rossini rarity. Produced in cooperation with the Rossini Foundation of Pesaro and supervised by eminent musicologist and Rossini scholar Philip Gossett, the revival brought reviewers from across the U.S. and Europe to Miami. Gianna Rolandi and Kathleen Kuhlmann offered brilliant coloratura in a trim but dramatic staging by director Francesca Zambello. Reviews, including one in the New York Times, were overwhelmingly positive and enthusiastic.

Despite their considerable successes, acrimony grew between Heuer and Waters with the conductor eventually being dismissed. Declaring that he wanted a “world famous conductor,” Heuer turned to Florida Philharmonic music director James Judd.

The Judd era lasted just three seasons. During that time, the Opera Guild of Fort Lauderdale (which had mounted its own productions) and the Miami company were merged into Florida Grand Opera.

Judd’s greatest contribution was a wonderfully eerie presentation of Benjamin Britten’s spooky ghost tale The Turn of the Screw. With Helen Donath giving the performance of her career as the Governess, this modern masterwork was both exhilarating and disturbing. Two Baroque operas planned by Judd brought star countertenor David Daniels in memorable performances of Handel’s Giulio Cesare and Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppaea (with a period-instrument ensemble in the pit).

Claiming he did not help sufficiently with fund raising for FGO, Heuer abruptly requested Judd’s resignation. Stewart Robertson, long associated with the Glimmerglass Opera in upstate New York, became music director. Despite an amiable demeanor, Robertson’s tenure marked an all-time low for the company’s artistic standards. With the Philharmonic facing troubled finances and, eventually, dissolution, a bargain-basement orchestra was hired. Despite the presence of some solid players, the ensemble was wildly uneven and could not play even the most familiar scores adequately. Robertson’s conducting was often pedestrian, the performances listless. Casting hit rock bottom. For a while, it seemed FGO could not find a tenor who could hit his high notes without strain.

There were a few bright moments even in this era, including Janacek’s Katya Kabanova (with soprano Oksana Krovytska giving a brave performance as the tragic heroine). An adventurous double bill of Ravel’s L’heure Espagnole and Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle was announced for January, 2004 but Robertson acquiesced in changing that slot to Donath’s Szulamit, not only conducting the 1899 Hungarian operetta but also making the English translation. Financed by a $600,000 contribution from the composer’s daughter, the work was musically trite and proved a major embarrassment for the company.

When Miami’s Arsht Center opened in 2006, FGO’s initial Aida utilized the same reduced orchestral forces as it had previously despite the large pit in the Ziff Opera House. Even in the gleaming new house, boring productions of familiar repertoire took up successive seasons. Eventually Robertson left in 2009, and Heuer retired in 2012.

Lauren Flanigan in FGO’s production of Marvin David Levy’s “Mourning Becomes Electra” in 2013. Photo: Lorne Grandison

Susan Danis, who had been executive director of the adventurous Sarasota Opera on Florida’s gulf coast, was appointed CEO and general director. Danis announced an ambitious agenda focusing on contemporary opera and rarely heard works as well as more familiar chestnuts. She imitated a series of offsite productions in unusual venues focusing on smaller-scale works.

An audit of the company’s finances found FGO had racked up more than $19 million dollars in debt between 2006 and 2013. A fund-raising campaign and public outreach initiative have been launched to reestablish the company’s financial stability and community involvement. The company says that they have closed the most recent fiscal year in the black, an encouraging sign.

On the artistic front, Danis’ initial offerings have yielded largely positive results. Mourning Becomes Electra brought a major American opera to South Florida stages. Music director Ramon Tebar led a fiery production of Verdi’s early Nabucco. The initial offsite offerings (a double bill of works by Robert Xavier Rodriguez and Piazzolla, and Andy Vores’ No Exit) were winners. Last season’s concluding production of Gian Carlo Menotti’s powerful Cold War music drama The Consul was cast and produced from strength.

It is that standard that FGO should continually aspire to as it looks to the future.

Rossini’s The Barber of Seville opens Florida Grand Opera’s season 7 p.m. Saturday night at the Arsht Center with Megan Marino, Andrew Owens, David Pershall and Kevin Short. Barber runs through November 21 in Miami and December 3 and 5 at the Broward Center in Fort Lauderdale. A second cast of principal singers (Hilary Ginther, Brian James Myer and Kevin Glavin) will sing the Nov 15, 20 and Dec. 3 and 5 performances. fgo.org; 800-741-1010.

Lawrence Budmen has been attending Florida Grand Opera performances for four decades, beginning with a 1972 production of Puccini’s La Boheme with Renata Scotto and Luciano Pavarotti.

Posted in Articles

One Response to “Over a tumultuous 75 years, Florida Grand Opera has seen its share of highs and lows”

Leave a Comment

Mon Nov 9, 2015

at 3:23 pm

1 Comment

Posted Jan 17, 2020 at 12:23 pm by Michael A Sturgulewski

I hope they do a Wagner opera SOON. Tannhauser or Lohengrin would be good choices..provided they’re done uncut and with traditional production.