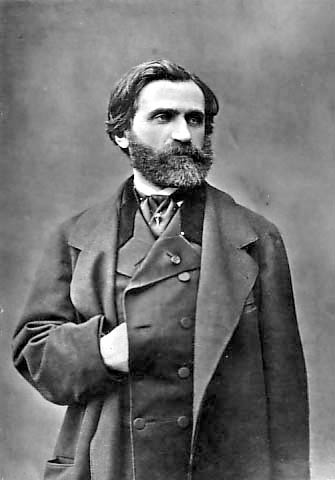

Sarasota Opera to celebrate the final season of Verdi cycle in style

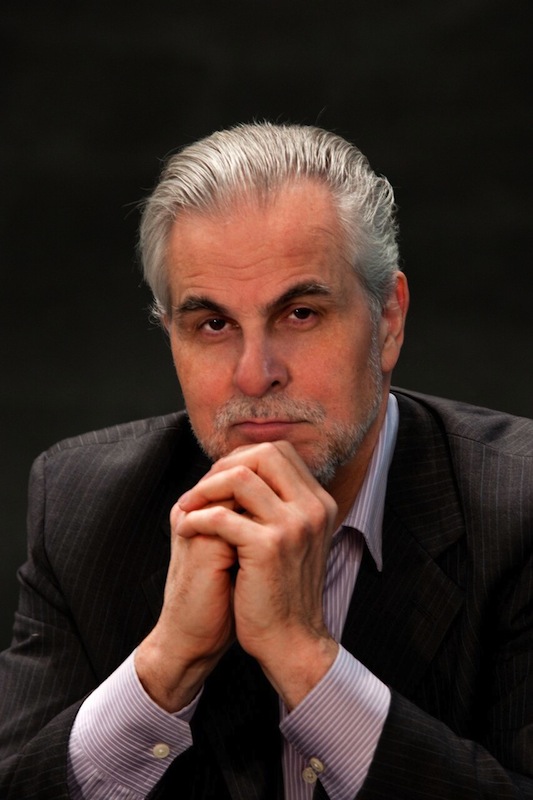

Victor DeRenzi will conduct “Aida” and “La Battaglia di Legnano” at Sarasota Opera to conclude the company’s long-running complete Verdi cycle. Photo: Giovanni Lunardi

A case can be made that every opera season is something of a Verdi festival.

Audiences and musicians alike respond to the Italian master’s unsurpassed gift for melody and high drama. Verdi’s name is always near the top, if not actually the first, on lists of the most frequently produced opera composers. It’s a safe bet that each year, somewhere on opera stages throughout the world, Violetta is breathing her last and Aida is standing by her man.

This season, however, Sarasota Opera is wrapping up a truly historic Verdi festival. With new productions of Aida and the rarely performed La Battaglia di Legnano, the company is closing its epic Verdi Cycle, a 28-year survey of the composer’s entire output, including his Requiem, String Quartet, and of, course, all his operas.

Since 1989 the company has presented every work Verdi wrote for the stage, more than 30 operas if you count the significant revisions Verdi made to four of the operas. Among these have been Don Carlos in both French and Italian versions, Le trouvere, the French retooling (with ballet) of Il Trovatore, and both the original and revised versions of Macbeth.

Scheduling one, sometimes two, operas for 28 consecutive seasons, Sarasota Opera has given opera lovers a rare chance to experience all of Verdi’s stage works in a relatively tight time frame. For hard-core fans, the chance to compare two versions of Verdi operas in a single season–Simon Boccanegra in 1992, La forza del destino in 1996 and Macbeth in 2003—offered a rare trip to an Italian Valhalla.

When Victor DeRenzi, the company’s artistic director and principal conductor, scheduled Rigoletto in 1989, he wasn’t planning to launch an epic survey of Verdi’s stage works.

“At first, it was a Verdi cycle, but not a complete Verdi cycle,” said DeRenzi during a phone interview earlier this month. “It was going to be a series of operas by Verdi. My audience had been asking for Verdi and I love Verdi; Verdi’s a great composer. At that time we had also added our Studio Artists program, which meant that for certain operas we could increase the chorus as we needed.

“After a couple of years,” DeRenzi said, “[we saw] how the audience reacted to, not only the popular Verdi operas, but also operas that many of them had not even heard of, like Aroldo [presented in 1990]. With that, it became the cycle for us to produce all of Verdi’s operas.”

“I was in the chorus for Aroldo,” said Richard Russell, Sarasota Opera’s executive director. His has a long history with the company, first joining as an apprentice artist in 1989 and returning as a principal artist through the mid-1990s. From 2005 to 2010 he was the company’s director of marketing before leaving for two years to become general director of the Opera Festival of New Jersey. He has held the top administration job at Sarasota Opera since 2012.

“Aroldo was important because of how the audience responded,” said Russell. “The audiences in those days in Sarasota were very restrained, to put it mildly. Sarasota is a retirement community, and it was a much older community than it is now. People were sparing with applause. But the audiences just erupted for that piece. That was the catalyst for doing all of this.”

In the mid-19th century, Italian patriots were agitating for the unification of Italy’s disparate states, and Verdi constantly battled with political censors. Composed in 1856, Aroldo is an adaptation of his Stiffelio, which had its premiere in 1850. Aroldo was initially acclaimed, but public ardor soon cooled, and today it is one of Verdi’s most rarely produced works.

“In the rarely heard Verdi,” said Russell, “people respond to the melodies but also to the wonderful ensemble and choral writing. The moment that we all remember in that [Aroldo] performance was the finale ensemble. It’s written so beautifully. I think that’s what people respond to.”

Sarasota Opera’s home is a former vaudeville and movie house dating to 1926. Not until a $20 million renovation in 2008, which expanded the auditorium to 1,129 seats, was the company’s orchestra pit large enough to accommodate big Verdi operas like Otello and Don Carlos.

Sarasota’s Verdi Cycle has not followed any chronological order. DeRenzi scheduled individual operas based on the availability of singers and an eye to choosing works that fit into the budgets and rehearsal requirements of the company’s annual four-production seasons.

Two elements have been constant throughout the cycle. DeRenzi insists on working with musical scores that reflect the most up-to-date scholarly research, and he has no use for so-called regietheater, productions created by stage directors who move the action to modern times and places.

In recent years, DeRenzi has worked closely with Francesco Izzo, co-director of the American Institute for Verdi Studies and general editor of the Works of Giuseppe Verdi, an ongoing publication of critical scores overseen by Verdi scholars.

“I’ve had a long association with Sarasota Opera,” said Izzo. “When I was still a graduate student at New York University I was responsible for running the archive of the American Institute of Verdi Studies. That’s when I met Victor DeRenzi. The Verdi Cycle was already underway, and he would call the institute on a regular basis to obtain materials or advice on specific projects. It was 2000 when I first visited Sarasota. We developed a very good working relationship.”

Izzo edited the critical edition of the score for Verdi’s second opera, Un giorno di regno (King for a Day), composed in 1840. Sarasota gave the world premiere of that edition in 2013.

“Verdi’s operas were quite popular,” said Izzo. “They circulated widely. They were recreated and copied. Very frequently materials were prepared in haste or they were prepared on the basis of other copies, so there’s an ongoing process of corruption. There’s also another question that is very important: sometimes Verdi’s works changed due to circumstances beyond his control, for example, the intervention of political or religious authorities. Sometimes Verdi’s choice was between a censored performance or no performance whatsoever.”

La Battaglia di Legnano (The Battle of Legnano), which Izzo calls “a very patriotic work,” was a case in point. Verdi wrote it in 1848 when Italy, like so much of Europe, was in extreme political turmoil. Focused on a battle in 1174 in which Italians in Lombardy rose up against Germanic rule, the opera set off alarm bells for Verdi’s Austrian censors. It had some performances in Rome, but to guarantee performances elsewhere, Verdi renamed the opera and moved the action to the Netherlands. After Italian unification in the early 1870s, the opera resumed its original form.

“Verdi was a practitioner,” said Izzo. “He was a very practical man. He accepted the status quo up to a point.”

Since 1982 when DeRenzi arrived at Sarasota Opera, he has been firmly committed to presenting opera in traditional productions. Sarasota audiences will not see Mozart played out in a contemporary Manhattan highrise or Verdi set in Las Vegas.

“We, as a policy, try to do Verdi’s intentions,” said DeRenzi. “Everything we do is Romantic if it’s a Romantic opera. That’s not only for Verdi, but it’s part of what this company is about. That’s something I believe in very much. In researching and preparing for a performance, we really go back to Verdi’s sources as much as we can, looking at original designs and reading letters, knowing as much as one can about it rather than just opening the score.

“I am firmly against modern productions,” DeRenzi continued. “I think they do great harm to the opera form. If we are losing audience in opera, it’s because of those productions that overlay some kind of interpretation that’s completely confusing and has nothing to do with the music and the text.”

Losing audiences wasn’t an issue for Sarasota’s Verdi Cycle. Performances often sold out, and audiences have included newcomers to the company. Russell recalls one hardcore Verdi fan from Ireland who first came in 2010 to see the rarely produced Giovanna d’Arco (Joan of Arc). He has returned every year since.

“We feel the cycle has been very positive for the company,” said Russell. “You expect Traviata and Aida and those [popular] things to sell well, but the thing that has been great for us is that we know we have a steady audience even for the rare Verdi. We have a credibility with audiences, Verdi has a credibility with them. People realize that even the rarely heard pieces have merit.”

La Battaglia di Legnano opens February 27 and runs through March 18; Aida runs through March 19. The season also offers Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte (through March 12) and Beethoven’s Fidelio (through March 11).

The Verdi Cycle will close with a concert of very early Verdi music March 17, a Verdi conference March 18-19 and a final concert preceded by a gala dinner March 20. sarasotaopera.org; 941-328-1300.

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Wed Feb 24, 2016

at 12:40 pm

No Comments