Composer Adams proves an excellent guide in New World’s contemporary program

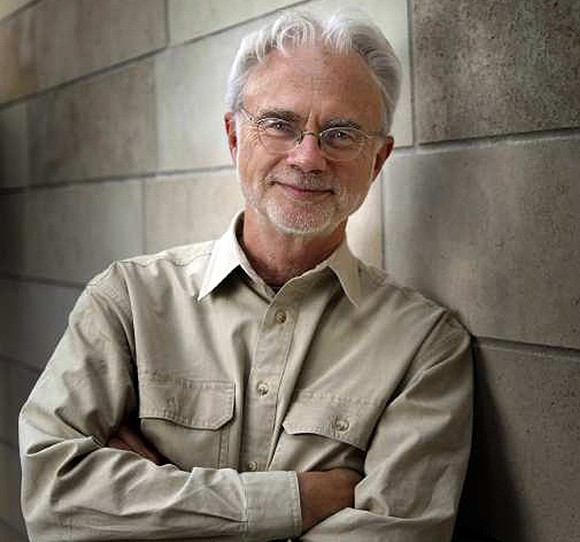

John Adams, the foremost living composer in the United States, strode on stage at New World Center Saturday night, slender and moving with the agility of a young man, despite his 71 years.

Adams led the New World Symphony in a concert of contemporary works that illustrated both the promises and challenges new music faces these days.

Although the Miami Beach hall was mostly full, the number of empty seats for a one-night-only appearance by a composer of Adams’ stature indicated that 21st century music still remains a tougher sell than Brahms and Tchaikovsky.

The program notes didn’t help matters. The explanations of the works in the composers’ own words made these pieces sound deadly—contrived and over-thought.

“I think of Flow as a series of connected textures that ebb and flow seemingly at random, but still in a greater context of a lucid, ineluctable movement,” wrote Ingram Marshall, of his 2016 work for piano and chamber orchestra. Samuel Carl Adams wrote of “exploring the intersection between naturally occurring acoustic resonance and digitally produced artificial resonance.”

But most of these works sounded better than the composers’ descriptions. And John Adams himself was an excellent guide, good-humored but serious, as he brought the composers on stage to talk about their works, helping listeners navigate the unfamiliar terrain.

“We’re so used to going to concerts and hearing the same music over and over in a sort of congenial laziness,” Adams said. “These pieces demand a different kind of listening.”

Adams contributed two short orchestral showpieces, which he joked counted as “early music” on this program, since they were composed in the 1980s.

A Short Ride in a Fast Machine, one of his most popular works, is an exhilarating whirl of notes, a wild ride within a rhythmic grid that seems about to give way at times. The New World musicians outdid themselves, with incisive, finely tuned playing that made every sharp turn apparent, building the music magnificently, with outstanding playing in the trumpets that topped the rushing sounds. Adams himself seemed genuinely impressed, saying afterwards, “Honestly, that Short Ride was one of the best I’ve ever heard.”

Adams composed his Tromba lontana (Distant trumpet) in response to a commission for a fanfare from the Houston Symphony. Rather than write the predictable few minutes of loud and brassy chords, he took a more subtle approach. This was a quiet work, with two solo trumpets, each stationed at one wing of the orchestra. They played just a few repeated notes, over hints of percussion and strings, with glassy violins and dark-hued lower strings creating a sense of depth and understated force, making the soft tones of the trumpet appearing distant not just in space but in time.

David Lang, co-founder of the New York indie-classical collective called Bang on a Can, says he was inspired to compose his tone poem mountain–he doesn’t use capital letters in his works–by the view of one from a summer cottage in Vermont.

In some program music, the connection between the sounds and what they’re describing can be elusive. Not here. The mountain, massive and unchanging, appeared via an extraordinarily rugged and resonant motif that repeated constantly through the work. Weighted and deep, anchored by the thump of bass drum and timpani and the growl of the tuba, it was topped by violins and flutes, providing a granite structure to the work. After a few minutes, a noble melody rose in the horns, as if to portray a hawk gliding overhead. Transparent stirrings in the winds created a delicate contrast, like mist or rustling leaves, as the mountain motif thundered on in this highly original and evocative portrayal of nature.

The American composer Timo Andres composed his Piano Concerto No. 3, titled “The Blind Banister,” as a response to a new cadenza Beethoven composed for his Piano Concerto No. 2, two decades after he originally composed the concerto.

It was difficult to detect any obvious connection to Beethoven. But in a way, this was the most conventional work on the program, with a formal structure that would have been familiar to Beethoven, even if he would have found the harmonies extra-planetary. The concerto also felt more connected to the Classical past in its melodic style and emotional tone, in contrast to the more abstract, cerebral sensibility of other works on the program. There were melodies, passages for solo piano and orchestra that built until the orchestra took over, and on another occasion, swelled to the pianist’s cadenza.

Performing the solo part was the pianist Jonathan Biss, for whom the work was composed and whose sensitive touch at the keyboard made the most of the concerto’s subtle moods.

Opening with the solo piano, performing lyric music with bittersweet harmonies, the concerto progresses in a meditative style, with spare playing in the piano. It is not a virtuoso work, but rather the opposite–inward-looking, personal and lightly orchestrated. The piano plays a light figures against chords in the upper winds. A descending two-note figure, like a series of sighs, repeats in the strings. A brief, boisterous inner movement appears, with touches of percussion. The ending appeared particularly enigmatic, without a hint that the music was nearing its close until it suddenly stopped.

Andres himself then served as piano soloist for Ingram Marshall’s Flow, a 2016 work premiered by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Composed using part of a New England hymn, the work was reminiscent of Ives, as the program noted, in the way the hymn fragments, drifts into pieces and still haunts the music. Starting quietly, it gains in power, as the simple motifs become more complex. It climaxed with grumbles at the bass end of the piano and wild playing on two marimbas.

The concert ended with many words of love, composed by Adams’ son, Samuel Carl Adams, a current composer in residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Of all the new works presented Saturday, this was the most difficult to grasp on first hearing.

The composer says the harmonies were “loosely based” on those of “Der Lindenbaum,” a song from Schubert’s bleak cycle Die Winterreise. But it was hard to hear any evidence of this, so the harmonies must have been fragmented to the point that they were unrecognizable.

This is a thickly orchestrated work. Even if a Mahler symphony requires large forces, Mahler’s music often required only a few instruments to be playing at once. But here, everyone seemed busy all the time. It’s full of passages that would start quietly and build through repeated figures, then fade away, without any apparent payoff, unless that was the fortissimo wash of sound with which the work concluded.

Adams is clearly a skilled orchestral craftsman, although the relentless density of the orchestration often seemed excessive. There were striking passages. At one point, trumpets soar over the surging orchestra. At another, a figure in the strings descends and then repeats and descends further, with each new figure appearing to be the lowest, until it goes lower still–an effective musical depiction of an abyss.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Sun Apr 1, 2018

at 1:10 pm

No Comments