Seraphic Fire spotlights the extraordinary music of Carlo Gesualdo

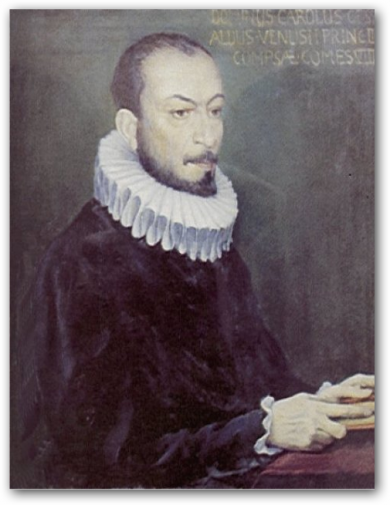

Carlo Gesualdo was a nobleman, a murderer and one of the most strikingly original composers of madrigals and sacred music in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Gesualdo’s works were the central focus of Seraphic Fire’s program “Chant for Male Voices” Thursday night at All Souls Episcopal Church in Miami Beach.

In typically adventurous manner, artistic director Patrick Quigley presented a musical recreation of a Tenebrae service. Taking place on the three nights prior to Easter morning, these Roman Catholic services marked the crucifixion of Jesus and the darkest hours of the Christian faith. Combining plainchant with the Lamentations of Jeremiah, Gesualdo’s pathbreaking responsory settings and works of other major church composers of the era, Quigley offered music for Holy Saturday.

The church’s long, narrow sanctuary was an impressive setting for this unique concert. With the high-ceilinged venue providing acoustical immediacy, the voices resounded with strength and directness. Quigley asked the audience not to applaud when the male choir took the platform or during the program to preserve the atmosphere of a religious service.

The story of Gesualdo’s life is dramatic and theatrical in itself. The Prince of Venosa (part of the Kingdom of Naples), he abandoned ecclesiastical studies and married his first wife Donna Maria in 1586. After persistent rumors of her unfaithfulness, he discovered her with her lover in 1590. Gesualdo immediately killed both of them brutally, dismembering their bodies. Despite an extensive police investigation, he was acquitted of the murders because of his noble rank. (Equal justice under the law was hardly a goal of that society or era.) He eventually went to Ferrara where he would study and work with some of the most important composers and musicians of the period. After remarrying he returned to Venosa and devoted himself almost totally to music but, besieged by guilt over the murders, he fell into depression. Eventually separated from his second wife, he died in 1613 under dubious circumstances. (Some biographers believe his wife, who had unsuccessfully sought a divorce, either killed him herself or had him murdered.)

The services for which Gesualdo wrote his sacred works were totally private. His court musicians played and sang his works for the solitary prince alone.

As Quigley’s presentation demonstrated, Gesualdo was over 300 years ahead of his time. In contrast to the spare chant and monody (single melodic paths) of religious composers of the era, Gesualdo’s music is replete with chromaticism and dissonance that would not appear again in music until the early 19th century. Such distinguished figures as Igor Stravinsky and conductor Stanislaw Skrowaczewski revered Gesualdo, composing and arranging scores based on his works.

Quigley fielded 13 singers for the program—nine choir members and four from Seraphic Fire’s ensemble artist program at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music. Divided into three parts or nocturnes, each segment opened with three antiphons. Austere vocal textures offer a sense of peacefulness. In Giaches de Wert’s De Lamentatione Jeremiae Prophetae, Quigley sang the solo vocal lines in a virile, warmly resonant baritone.

Following such traditional plainchant, Gesualdo’s music was shocking in the most positive manner. His harmonies seemed to come from another world entirely. In contrast to the simple fragmentary vocal lines of the lamentations, the wild leaps and surprising emotional contours of Gesualdo’s Jerusalem, surge (Arise, O Jerusalem) were stunning for their sheer originality. Even for the high male voices, the vocal writing falls to the lowest register in Gesualdo’s Piange quasi virgo (Mourn as a virgin) as the singers command the priests to cover themselves in ashes. Gesualdo plays against the text with music that is almost calm and ethereal for Astiterunt reges terrae (The kings of the earth rise up). The boldly inventive and consistently engrossing music of Gesualdo remains singular.

Although more conservative, the rise of joy from solemn depths in Orlando di Lasso’s Auditui meo dabis guadium et laetitiam (Thou will make me hear of joy and gladness) was palpable in the choir’s full-voiced, deeply felt performance. For sheer beauty of melodic inspiration, Palestrina’s Benedictus Domininus (Blessed be the Lord) was the evening’s gem with Quigley exquisitely calibrating the blended timbres. The rising musical strokes of Giammateo Asola’s Christus factus (Christ became obedient to death), which concluded the evening, seemed to anticipate in spirit of the Resurrection that was to come.

Quigley’s leadership throughout this difficult, stylistically varied repertoire was unerringly effective and attentive to dynamic variety and unified vocal production. The skills of the singers was tested to the limits in this demanding program and they came through it, thrillingly, with flying colors. Special credit to countertenors Doug Dodson and William Duffy for their command of the seemingly impossible high tessitura in many of Gesualdo’s scores.

Once again Quigley has conceived and produced a one-of-a-kind program. There are three remaining performances for this rare opportunity to hear some of the most unique music ever written.

Seraphic Fire repeats the program 7:30 p.m. Friday and 4 p.m. Sunday at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Coral Gables and 7:30 p.m. Saturday at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale. seraphicfire.org

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Fri Nov 9, 2018

at 12:50 pm

No Comments