Seraphic Fire to start season at the 12th century with Hildegard of Bingen

Many people, even some musicians, think that music history begins with J. S. Bach.

Such is not the case with Patrick Dupré Quigley, founder and artistic director of Seraphic Fire, the Miami-based choir that ranges far more widely in their concerts than most ensembles.

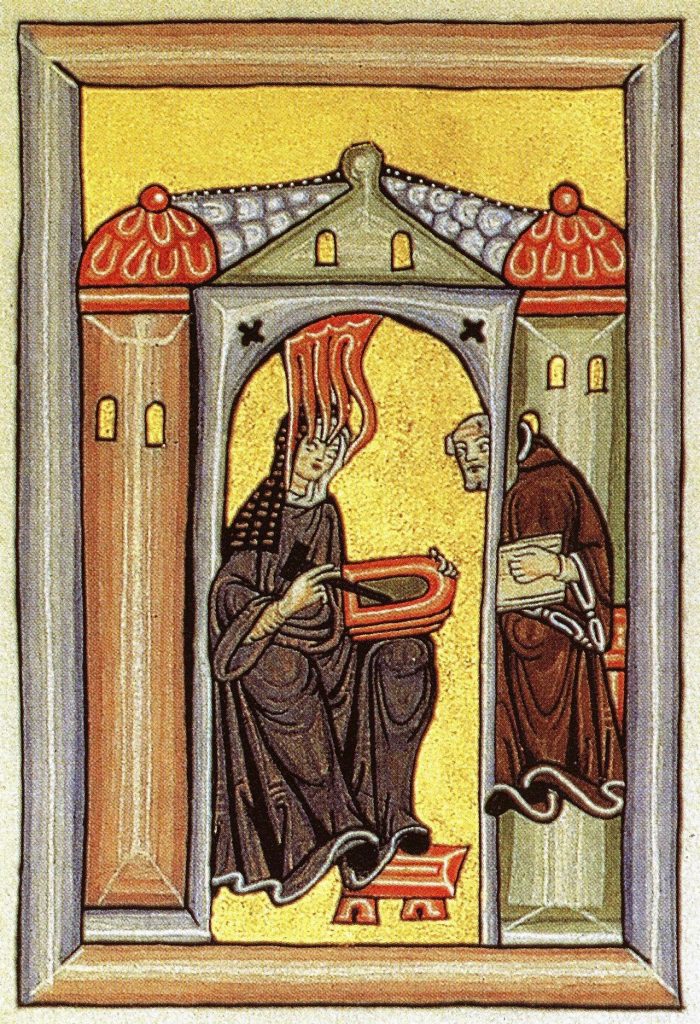

To open their 18th season, the elite choral ensemble will take listeners to a remote 12th-century convent in the Rhineland. The women members of Seraphic Fire will perform the allegory play Ordo Virtutum by medieval abbess, philosopher, and composer Hildegard von Bingen.

Quigley thinks listeners will be surprised at how modern the work sounds. “This is certainly the Miami premiere of the work,” he said last week. “Probably the Florida premiere. Only 900 years later, we are bringing you the greatest hits of the 12th century,” he added with a laugh.

“We have been looking for something to showcase our soprano and alto sections for a long time, and I think this is the perfect vehicle for it,” he said.

Hildegard wrote the words and the melodies of the play for the nuns of her convent. The occasion for the performance is not clear. “This music was written for a specific group of people,” Quigley explains, “for a specific cast, and probably for a specific time. A lot of things point to this being written for the celebration of the dedication of Hildegard’s new convent at Rupertsberg on the Rhine.”

The Order of the Virtues, as the title is normally translated, concerns the struggle of a woman called Anima, a nameless human soul torn between the temptations of the world and a virtuous life. Many of the characters are allegorical representations of the virtues. The work may reflect the experience of Hildegard herself, dedicated to the religious life by her family when she was a young girl. Another theory is that the work was revived in the monastery when a new nun took vows and joined the convent.

Although the work had a specific monastic origin, Quigley maintains the work’s relevance to a modern audience. “The play is not Christian in a way,” he says. “There’s no Jesus, there’s no Mary. It’s about a virtuous life versus a life of excess. I can’t think of a time when that is more appropriate than this decade of the 21st century.”

“Every person is pulled between different poles,” he continues. “This is a story about how one person makes a choice. It’s teaching a lesson, which is ‘Let us choose music, let us choose vibrancy, let us choose higher things rather than the obvious and base’. I don’t think that is limited to a religious perspective. It’s a philosophical play more than it is a religious play.”

“Here is a soul who is choosing between this free and wonderful world of the Virtues or this enticing world of base instincts that the devil is offering,” he elaborates. “The Devil, pointedly, does not sing. There is no music in the Devil’s world, so the Anima, this female spirit, is choosing between music and not-music. She eventually chooses music, which is in many ways what Hildegard decided. Hildegard decided that she was going to be heard.”

Quigley thinks audiences may be surprised by the lushness of the music, too. “The freedom of the lines of music that Hildegard writes” is striking, he explains. “Particularly the chants in the Ordo are liberated in how they treat the chant modes. The vocal range extends from the A below the treble staff to the A or B-flat above the treble staff, so much more daring” than earlier medieval chant.

Hildegard was writing in the accepted style for music in a convent—sung chant without any notated instrumental accompaniment. “But Hildegard followed her conscience,” Quigley says. That doesn’t mean “that she didn’t follow the rules, but that she was following the ecstatic visions she claimed to have had since she was a young woman.” In 2012 Pope Benedict XVI made Hildegard’s canonization as a saint official, also naming her a Doctor of the Church for her theological writings.

Some performances and recordings of the Ordo try to fill out the piece, adding polyphonic parts to create harmonies or fanciful instrumental accompaniments. “We are actually just performing the notes that she wrote,” Quigley adds. “The notes and the words were hers, entirely a composition that is original to her. It’s very ecstatic poetry, that is, the lyrics of this music, and it’s very stark in the allegorical treatment of the characters.”

Hildegard’s independence was certainly striking for a woman in her era. “She is a full generation before the Notre Dame School of organum,” he says, referring to the early polyphonic school that includes some of the earliest named composers. “Yet she has so many pieces attributed to her, in addition to being the first major attributed composer. She is the mother of the idea of copyright and ownership of music and text. She was very intent that her music would be attributed to her and that it had lasting potential, so much so that she wrote much of it down.”

Quigley and his singers wanted to get as close as they could to the music’s medieval origins. He has worked with Honey Meconi, musicology professor at the Eastman School of Music and author of a recent biography of the composer, to understand the issues. “It’s not like performing a later piece like The Marriage of Figaro,” he jokes, “where you are deciding if you are going to set it on the moon. We have the notes, we have the order of the notes, we have the words that go under the notes: now what?”

They started with the transcription of the music by Audrey Ekdahl Davidson, published and revised in the 1980s. “It’s a great edition,” says Quigley, “because she makes no assumptions about rhythm. She lays out the melody, she shows where the ligatures connected the neumes.” They used guidelines from another scholarly book, Singing Early Music, for information on how to pronounce Latin as Rhenish singers likely pronounced it.

Still, the group will make a few small additions. “There will be some drones,” Quigley says, “but those will be for effect rather than as an entire thing. We will have a pitched instrument. They may have used bells or various things; we’re using crotales.”

In part to provide an example of how Hildegard’s music differed from earlier styles of Gregorian chant, the concert will begin with the proper chants for the medieval Mass of Dedication of a Church. “The one man who will perform with us is James Bass, our associate conductor,” Quigley notes. “He will sing the priest role and then will take on the role of the Devil for the second half of the program.”

There will be semi-staging in the performance, as there probably was in the Middle Ages. Although there will be no sets, Quigley explains, “there will be some costuming, more sort of color-based. It requires movement, and some allegorical things needed to be visually represented, like the binding of the Devil or the spirit coming of age in the world, then leaving the world and coming to the Virtues to become part of this community.”

Starting with the music of the Mass puts the Ordo in its liturgical context. “Probably the Mass would have finished,” Quigley speculates, “and then everyone would have sat down and the nuns would have put on a show. This work is the missing link. This is when music crawls out of the ocean, is identified as a species. This is when it’s happening. We get to see that. Every hour that I spend with this music, it becomes more interesting, which is why I think it’s great art.”

Seraphic Fire performs Hildegard von Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum 7:30 p.m. Wednesday in Miami, 7:30 p.m. Thursday in Boca Raton, 7:30 p.m. Friday in Coral Gables, 7:30 p.m. Saturday in Fort Lauderdale, and 4 p.m. Sunday in Miami Beach. seraphicfire.org

Charles T. Downey is the Lead Critic and Associate Editor of Washington Classical Review. He also reviews concerts for the Washington Post and is a long-time observer of classical music and the arts in the nation’s capital.

Posted in Articles

Leave a Comment

Mon Nov 4, 2019

at 1:50 pm

No Comments