Master Chorale marks Beethoven anniversary with a rich, dramatic Ninth

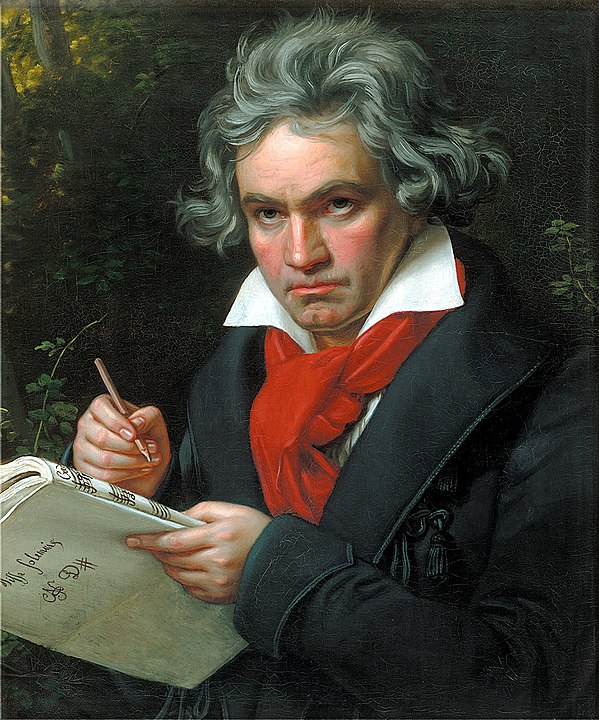

A concert tribute to Beethoven Wednesday night focused on two pillars of his reputation: the mammoth Symphony No. 9 and the cruel irony of a great composer going deaf.

The Master Chorale of South Florida, conducted by artistic director Brett Karlin, performed at Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale. On stage with the chorus was the Lynn Philharmonia, a student ensemble from Lynn University’s highly esteemed Conservatory of Music.

The concert, another in a series of observances of the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, opened with A Silence Haunts Me, a work inspired by Beethoven’s words and music by the American composer Jake Runestad.

The 2018 piece for chorus and piano contains words by the poet Todd Boss inspired by Beethoven’s famous 1802 Heiligenstadt Testament, an unsent letter to his brothers in which he describes his determination to carry on and meet his fate bravely, despite the hearing loss that reduced his ability to experience music and companionship.

The work opened with clanging, dissonant notes on the piano, performed by Susan Dodd, perhaps expressing the composer’s impending deafness and his own frustration. “Here me, oh brothers,” the chorus sang, “I have a confession – painful to make. Six years I have endured a curse that deepens every day.”

Runestad’s work quotes Beethoven’s “Moonlight” sonata, the Funeral March from the Symphony No. 3 and a fragment of the Ninth Symphony’s Ode to Joy. But Runestad’s voice predominated, as the chorus sang tones of quiet, soft-edged comfort, with stirring ascending passages that seemed to indicate the composer’s triumph over despair in a moving tribute to Beethoven’s spirit. The work faded away, as Karlin conducted long silent rests, indicating Beethoven’s entrance into the soundless world he had feared, but with the bravery expressed in the chorus.

With a student orchestra—even one made up of advanced instrumentalists such as the Lynn musicians—one never knows what to expect. But the Lynn Philharmonia played the Ninth Symphony with a high degree of skill, producing a rich orchestral sound in an energetic performance that spanned the symphony’s journey through menace, violence, serenity and joy.

They delivered a taut and dramatic account of the opening Allegro, but the performance had one serious flaw: The brass were way too loud. This happens sometimes, even in professional orchestras, but the problem was pervasive throughout the movement; since much of the thematic material is in the violins, this important music was often covered up. The problem worsened toward the final climax, where violins were visibly playing busily but it was hard to hear any notes.

The complex counterpoint of the Molto vivace was admirably clear and pointed, as the different sections entered, with an edge of nervy energy. The orchestra played with boisterous verve as the music brightened.

The Philharmonia members captured the serene, lofty spirit of the Adagio. The running figures in strings came off with lyric sweep and a fine sense of phrasing. Winds played in a natural, songlike style, with rounded, well-blended tones.

The grim brass and wind fanfare that opens the Finale arrived with violent force, effectively setting the stage for the drama to come. Cellos and basses played their extended recitative with brawny power and an expressive, operatic manner. The first appearance of the Ode to Joy theme was unusually quiet, giving the famous melody effective understated weight.

The bass baritone Richard Ollarsaba gave a boldly forceful account of his opening words that shift the direction of the symphony toward its triumphant conclusion. He sang with darkly gleaming tones. Equally effective was the tenor Robert Stahley, who brought an urgency and intensity to his part that contrasted with the weight of Ollarsaba’s singing. The soprano Sherezade Panthaki and mezzo-soprano Rebecca Robinson topped the choir with rich, agile, shimmering tones.

The 130-voice choir produced a huge sound. The singers nimbly negotiated Beethoven’s sudden pianissimos and abrupt crescendos. Toward the end of the movement, they brought stark force to ascending passages, and they delivered the jubilant, triumphant tones that redeem the symphony’s earlier darkness.

The Master Chorale of South Florida performs Mendelssohn’s Elijah May 1 and 3. masterchoraleofsouthflorida.org

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Thu Feb 27, 2020

at 1:11 pm

No Comments