Schwarz, FSO pay homage to Peter Mennin in centenary year

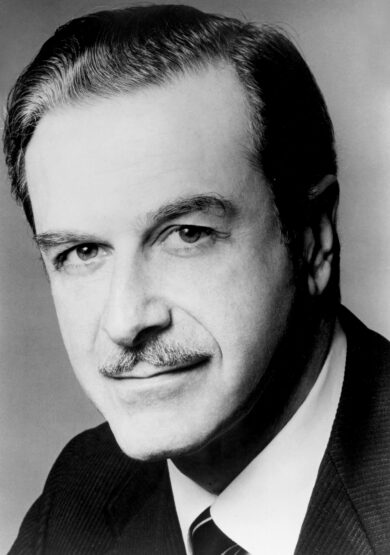

Gerard Schwarz is one of the few conductors who have paid any consistent attention to American composer Peter Mennin, with recordings of some of Mennin’s orchestral music when he was director of the Seattle Symphony.

Schwarz conducted the Frost Symphony Orchestra in the composer’s Moby Dick Saturday night in Gusman Concert Hall, but it was more than a throwback to his professional history—this year is Mennin’s centennial, and the performance (viewed through livestream) might be the only one honoring the composer this year.

In a likely unintentional trajectory, Moby Dick opened the concert and set a high mark from which the rest of the evening gradually descended. The world premiere of Lansing McLoskey’s Violin Concerto followed with Frost alumnus Miclen LaiPang soloing, and after intermission Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5.

Mennin was one of the finest of the group of post-Ives American modernist composers that extended from the likes of Carl Ruggles, Roy Harris, and Ruth Crawford Seeger to William Schuman, David Diamond, and Walter Piston, one that arguably hit a wall with Leonard Bernstein. They defined a unique American sound, an urban one parallel to Copland’s mythical ruralism, through a substantial body of great orchestral music. Yet since Bernstein’s death they have been almost completely, and shamefully, ignored by the American classical music establishment.

The orchestra’s focused, energetic performance of Moby Dick showed what the world has been missing. More of an impression of the novel in overture form than a narrative, the piece is emblematic of Mennin and, more broadly, this American style. The extended tonal harmonies have a robust richness at any volume, the contrapuntal lines are elegant, and the way the music develops from the lovely, delicate opening flute solo is extremely skillful. The music expresses not just drama but the complex emotions of the American aesthetic, figuring out what it means to be an American, and a modern, artist.

The players seemed to feast on this. The playing was not just physically energetic but expressive, with the sense that the music was personally meaningful and fulfilling to the orchestra. With Schwarz’s knowledgable direction, the players carried the excitement of discovering music that could balance intelligence, muscle, and heart.

Speaking from the stage, McLoskey gave a general description of his new concerto, explaining how the kernel of the music was the hymn “The Holy City,” pointing out the unusual four-movement form—with only two movements featuring the soloist. With movements flowing one into the other, this did come across as two large sections.

With LaiPang playing with a singing, strong tone, flow was the strength of the piece, especially the opening half where the music seemed to represent icebergs on the ocean, slowly approaching and melding with each other. The opening half was spacious and still, the second not just more active but the place where the violinist got to show his dexterity. The solo part here had an invigorating mix of pizzicato and arco passages, set against the orchestra’s syncopations. There was an uncomfortable gap here between LaiPang’s technique and confidence and an orchestra that was often struggling with their parts.

One wished for a more measured feeling throughout, not necessarily a longer duration but the chance to hear more of the core ideas. The sense that the music was mostly development was at times involving but at others confusing.

For an encore, LaiPang came back out with his former teacher, violinist Charles Castleman. The two played an arrangement of the Gigue from Bach’s Partita No. 2, mixed with other sections from the piece. It began as a lively duo and was at first intriguing and musically smart, but the playing grew so sloppy as it went along that it ended up being merely clever.

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 took some time to get going. The opening statement of the central, “fate” theme was colorful and mellow, but there wasn’t enough tension in the opening movement. Tchaikovsky doesn’t often have the most compelling harmonic structure, and needs a commitment to melody and emotion to move forward, and those weren’t sufficient until the moment of dramatic crisis in the second movement. That seemed to spark the young musicians. The third movement waltz didn’t have great bounce, but the energy through the end of the performance proved satisfying.

Posted in Performances

Leave a Comment

Sun Dec 3, 2023

at 2:51 pm

No Comments